Zhu Bajie : The Pig Warrior of Journey to the West

Listen

At a glance

| Description | |

|---|---|

| Origin | Chinese Mythology |

| Classification | Hybrids |

| Family Members | Gao Cuilan (Wife) |

| Region | China |

| Associated With | Gluttony, Laziness, Lust |

Zhu Baije

Introduction

Zhu Bajie, often called Pigsy in English translations, stands as one of the most beloved and morally complex figures in Chinese mythology. Originating from Wu Cheng’en’s 16th-century masterpiece Journey to the West, Zhu Bajie’s story weaves comedy, tragedy, and spiritual symbolism into one unforgettable narrative. Before his fall, he was known as Marshal Tianpeng, a celestial general who commanded the Heavenly Navy. His downfall came after drunkenly flirting with the Moon Goddess, Chang’e, leading to his expulsion from Heaven and reincarnation as a half-man, half-pig creature.

Condemned to the mortal world as a pig demon, Zhu Bajie was later recruited by the Bodhisattva Guanyin to accompany the monk Tang Sanzang (Xuanzang) on a sacred pilgrimage to India to retrieve Buddhist scriptures. Throughout the journey, he represents the flawed side of human nature—greedy, lazy, and lustful—but also compassionate and loyal. His story mirrors the Buddhist path of redemption, showing that enlightenment can be achieved even by those burdened with weakness and desire.

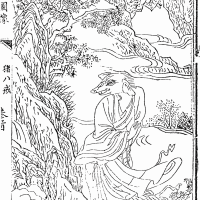

Physical Traits

Zhu Bajie’s appearance perfectly embodies his inner struggle between divine potential and earthly indulgence. He has the face of a pig with a large snout, floppy ears, bristled cheeks, and small tusks. His body is rotund and heavy, symbolizing both gluttony and earthly attachment. Despite his grotesque form, he often tries to act refined, particularly around women, creating a humorous contrast that has made him a cultural icon of self-delusion and desire.

His attire typically consists of monk-like robes tied at the waist, signifying his incomplete spiritual transformation. The mix of holy clothing and a beastly body reflects his position between the sacred and the profane. He wields a distinctive weapon—a massive nine-toothed iron rake (jiǔchǐdīngpá)—which doubles as both a farming tool and a divine instrument of war. This rake represents transformation through labor and discipline, reminding readers that even base instincts can be turned toward higher purposes when guided by faith.

Family

Zhu Bajie’s family relationships reveal both his human longing and his demonic past. Before his banishment, as Marshal Tianpeng, he was a respected celestial being without family obligations. After his reincarnation, however, his animalistic birth led to a violent beginning—he was born to a sow and devoured his pig siblings. Seeking stability, he settled in Gao Village under the name Zhu Ganglie, where he courted and married Miss Gao, the daughter of a local elder. Although his deception was eventually exposed, this episode highlights his desire for companionship and normalcy despite his monstrous nature.

Within the pilgrimage group, his relationships form a kind of spiritual family. Tang Sanzang acts as his mentor and moral guide, Sun Wukong (the Monkey King) as his rival and counterpart, and Sha Wujing as the patient mediator. Their dynamic represents the human condition in miniature—discipline, desire, and endurance all working toward enlightenment.

Other names

Zhu Bajie is known by several names that mark the stages of his spiritual and moral evolution. His celestial title, Marshal Tianpeng (天蓬元帅), signifies his position as commander of Heaven’s naval forces. After his fall, he became known as Zhu Ganglie (猪刚鬣), meaning “strong-maned pig,” emphasizing his raw and untamed nature. When Guanyin introduced him to the Buddhist path, she gave him the name Zhu Wuneng (猪悟能), or “Pig Awakened to Ability,” implying self-awareness and potential for redemption.

Finally, Tang Sanzang bestowed upon him the monastic name Zhu Bajie (猪八戒), which translates to “Pig of Eight Commandments.” The “Eight Precepts” refer to Buddhist moral rules—against killing, stealing, lying, intoxication, sexual misconduct, and other impurities. This name serves as a daily reminder of his struggle to control his base instincts. In Japan, he is called Cho Hakkai; in Korea, Jeo Palgye; and in Thailand, Tue Poikai, reflecting his widespread cultural influence across Asia.

Powers and Abilities

Though often portrayed as comic relief, Zhu Bajie is far from powerless. Before his fall, he was a fearsome warrior with command over celestial forces, particularly skilled in naval and aquatic combat. On Earth, he retains great physical strength—capable of performing the labor of dozens—and wields his iron rake with devastating power. His weapon, forged from divine ice steel and engraved with heavenly sigils, symbolizes his enduring link to his celestial past.

He possesses the ability to perform 36 transformations, though these are clumsy compared to Sun Wukong’s 72 forms. Zhu Bajie’s transformations tend to produce massive or awkward shapes, underscoring his imperfect mastery of spiritual arts. He can also fly using cloud-riding techniques, though much slower than his peers. His supernatural endurance and resistance to injury make him an effective, if reluctant, warrior. Yet, his greatest obstacle remains internal—his laziness and greed often prevent him from achieving his full potential. In Buddhist allegory, this symbolizes the struggle to overcome attachment and ignorance in pursuit of enlightenment.

Modern Day Influence

Zhu Bajie’s legacy has flourished across centuries of literature, theatre, film, and digital media. In traditional Chinese opera, he is depicted as a comic yet endearing figure whose appetite for food and love masks an underlying wisdom about human nature. Countless film and television adaptations of Journey to the West continue to reimagine him—from the classic 1986 CCTV series to modern reboots that present him as both a fool and a philosopher.

In popular culture, Zhu Bajie’s image appears in anime, comics, and video games. The Japanese manga Saiyuki reinterprets him as the character Cho Hakkai, a calm and intelligent version of the pig spirit. In gaming, Zhu Bajie features as a playable hero in Smite, Warriors Orochi, and Black Myth: Wukong, where he is portrayed as a loyal companion seeking redemption for his past. His name has also entered everyday language—calling someone a “Zhu Bajie” in Chinese colloquial speech means they are greedy or foolish, a humorous nod to his enduring archetype.

Interestingly, Zhu Bajie has even taken on minor religious significance in parts of East Asia. In certain Chinese folk traditions, he is regarded as a patron figure for workers in the hospitality and entertainment industries—those living on society’s margins—reflecting empathy for imperfect yet kind-hearted individuals.

Zhu Bajie’s charm lies in his humanity. He is neither purely virtuous like Tang Sanzang nor fully divine like Sun Wukong. His failings—lust, hunger, laziness—mirror the everyday struggles of ordinary people. Yet, despite these flaws, he continues his journey, helping his companions reach their spiritual destination. His story is a testament to the idea that enlightenment is not the absence of imperfection, but the perseverance to rise above it.

Through centuries of retellings, Zhu Bajie remains one of Chinese mythology’s most relatable and enduring characters—a humorous yet profound reminder that even the most flawed beings can walk the path toward redemption.

Related Images

Source

Brose, B. (2018). The Pig and the Prostitute: The Cult of Zhu Bajie in Modern Taiwan. Journal of Chinese Religions, 46(2), 167–196.

Wu, C. (Trans.). (1592/2020). Journey to the West. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press.

Wikipedia. (2025). Zhu Bajie. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zhu_Bajie

YouWeiTrade. (2024). Zhu Bajie’s Story. Retrieved from https://youweitrade.com/blogs/blog/zhubajies-story

The World of Chinese. (2019). The Many Faces of Zhu Bajie. Retrieved from https://www.theworldofchinese.com/2019/02/the-many-faces-of-zhu-bajie/

Journey to the West Wiki. (2024). Zhu Bajie Character Profile. Retrieved from https://journey-to-the-west-xiyouji.fandom.com/wiki/Zhu_Bajie

Myth in Media Wiki. (2007). Zhu Bajie. Retrieved from https://myths-in-media.fandom.com/wiki/Zhu_bajie

Amino Apps. (2023). Zhu Bajie Profile: Fate & Nasuverse Wiki. Retrieved from https://aminoapps.com/c/fatenasuverse/page/item/zhu-bajie/0koq_vnfZIjl5vB10xDzEDn5vlqwz5Vglz

Wu, C. (1993). Journey to the West (A. Yu, Trans.). University of Chicago Press.

Idema, W. L. (2012). Chinese Vernacular Fiction: The Journey to the West. Harvard University Press.

Yang, L. (2005). Handbook of Chinese Mythology. Oxford University Press.

Teo, S. (2009). Chinese Mythology in Popular Culture. Routledge.

Wang, D. (2010). The Monster That Is Zhu Bajie: Comic Relief and Moral Ambiguity in Journey to the West. Journal of Chinese Literature and Culture, 2(1), 45–67

Frequently Asked Questions

Who is Zhu Bajie in Journey to the West?

Zhu Bajie is one of Tang Sanzang’s disciples, a pig-like warrior who provides strength, humor, and occasional trouble on the pilgrimage.

What was Zhu Bajie before joining the pilgrimage?

He was once a Marshal of Heaven but was banished to Earth for misbehavior, transforming into a pig demon before earning a chance at redemption.

What does Zhu Bajie represent?

He embodies human weaknesses such as laziness, gluttony, and lust — yet also loyalty and bravery when it truly matters.

What weapon does Zhu Bajie use?

He wields the Nine-Toothed Rake, a powerful farming tool turned mystical weapon capable of taking down demons and enemies.

Why is Zhu Bajie such a popular character?

His humorous personality, relatable flaws, and heartfelt growth make him one of the most beloved characters in the entire legend.