Chantico : The Aztec Goddess of Fire, Home, and Forbidden Power

Listen

At a glance

| Description | |

|---|---|

| Origin | Aztec Mythology |

| Classification | Gods |

| Family Members | Xiuhtecuhtli (Father) |

| Region | Mexico |

| Associated With | Fire, Kitchen, Household |

Mythlok Perspective

From the Mythlok perspective, Chantico represents elemental fire in its most intimate form, not as chaos but as responsibility. Her story aligns closely with hearth deities across cultures, such as Hestia in Greek tradition and Agni in Indian belief, where fire sustains order when respected. Across civilizations, sacred fire consistently appears as a test of discipline, revealing a universal truth that power begins at home and must be governed before it can illuminate the world.

Chantico

Introduction

Chantico, derived from the Nahuatl term meaning “she who dwells in the house,” stands as a prominent deity within Aztec mythology, presiding over the sacred fires of the family hearth. This divine entity extends her influence beyond the domestic realm, also being associated with the town of Xochimilco, stonecutters, and warriorship. Worship of Chantico unfolded in the sacred precincts of a temple known as a “te tl an ma n,” where devoted priests diligently prepared offerings for her ceremonial feasts.

Renowned as both the tender guardian of the hearth and the formidable force driving volcanic eruptions, Chantico embodies the dualities of warmth and wrath, comfort and destruction. In the expansive pantheon of Aztec gods, she holds a significant and revered position, acknowledged as the goddess of hearth, warmth, and precious possessions.

Physical Traits

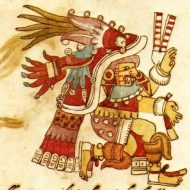

Within the Codex Borgia’s vivid illustrations, Chantico emerges with distinctive features, her countenance painted in hues of yellow, accentuated by two striking red lines—a symbolic designation of her status as a fire goddess. Her body, also bathed in yellow, contributes to the portrayal of her divine essence. Adorned with a headdress that bears military symbolism, Chantico’s crown boasts poisonous cactus spikes, evoking notions of danger and aggression, while a crest of aztaxelli, adorned with green warrior’s feathers, establishes a connection with the realm of warfare.

Although depictions of Chantico exhibit variations, certain recurring elements define her visual representation. Frequently portrayed as a youthful woman, her skin emanates an ember-like glow, and her hair becomes a cascade of flames. A crown fashioned from sharp cactus needles graces her head, serving as a poignant reminder of the potential sting associated with her embrace. Around her neck, a serpentine figure made of fire dangles, its forked tongue symbolizing the capricious and unpredictable nature of her elemental domain. In the midst of swirling flames, she dances, her red skirt mirroring the billowing smoke, while her bare feet delicately graze the scorching ground. Some depictions even showcase her transformative nature, as she metamorphoses into a fiery serpent, her scales shimmering with molten gold and crimson brilliance.

Family

Chantico, a figure of considerable significance in Aztec mythology and religion, was perceived as the sister of Xiuhtecuhtli, the revered god overseeing both fire and the sun. The narrative surrounding Chantico’s origins is veiled in mythic tales, and one such account traces her emergence from the smoldering remnants of Cipactli, the primordial monster credited with birthing the world. Acknowledging her fiery spirit, her father, Xiuhtecuhtli, the Fire God, nurtures her within the depths of Mount Popocatépetl, solidifying her connection to the earth’s molten fury through the volcano.

Various myths interweave Chantico’s lineage with other deities such as Huehuetóteotl, the Old Fire God, and Xolotl, the God of Twin Fires and Duality. Regardless of the specific parentage attributed to her, Chantico remains intrinsically linked to the very essence of fire—an elemental force both primal and transformative in nature.

Other names

Chantico, recognized by various names that encapsulate different facets of her divine essence, is also referred to by her calendric designation, Chicunaui itzcuintli (Nine Dog). Additionally, she carries the titles of “Lady of the Capsicum-Pepper” and “yellow woman.” Among stonecutters, she assumes the names Papaloxaual (Butterfly Painting) and Tlappapalo (“she of the red butterfly”). While the name Chantico itself, meaning “She who dwells in the house,” aptly signifies her role as the guardian of the hearth, her alternative appellations unveil diverse dimensions of her character.

Xocotzin (“Little Corn Goddess”) intertwines her identity with themes of fertility and abundance, while Tlacotēpēc (“Flint Woman”) resonates with her connection to war and sacrifice. Yet another name, Itzpapalolotl (“Butterfly Goddess of Obsidian”), symbolizes the transformative aspects of fire, aligning Chantico with the cyclical nature of life and death, reminiscent of the metamorphosis and rebirth associated with butterflies. Each name contributes to the rich tapestry of Chantico’s multifaceted nature, reflecting the depth and diversity of her influence in Aztec mythology.

Powers and Abilities

Chantico wields the formidable power of fire in its myriad manifestations. At the hearth, she tends to the gentle warmth, ensuring the provision of sustenance, comfort, and illumination. Yet, within her divine essence resides the unrestrained might of volcanoes, capable of convulsing the earth and unleashing molten fury. Chantico stands guard over homes, warding off intruders and dispelling darkness, yet her fiery essence also possesses the capacity to scorch and consume with an unyielding heat. Her gaze has the power to kindle passions or instill fear, and her touch can alternate between soothing comfort and searing intensity.

Chantico transcends being merely a goddess of fire; she embodies fire itself—a capricious force capable of both nurturing and destroying. Initially recognized as a domestic deity closely tied to the fires of the household hearth, she assumed the role of the guardian of homes and their contents. Through an expanded understanding of her influence, the Aztecs began to perceive her as the protector of their entire empire, a testament to the encompassing and pervasive nature of her divine prerogatives.

Modern Day Influence

Chantico’s impact transcended the realm of mythology, weaving into the fabric of everyday life for the Aztecs. Revered as the goddess of hearth fires, her presence graced many Aztec households, where her image symbolized a blessing upon the home. Additionally, Chantico held ties to sacrificial rituals, earning homage during religious ceremonies. Her fiery spirit resonated deeply with those embracing passion, creativity, and transformation. Feminist interpretations further highlighted her strength and independence, challenging established gender norms.

In today’s intricate world, Chantico’s duality remains relevant, serving as a poignant reminder of the delicate equilibrium between nurturing energies and destructive forces. Beyond its portrayal in art, her legacy endures in traditional Mexican customs. Offerings, often in the form of chili peppers representing her fiery essence, are presented to her in various rituals. This influence extends even to the culinary domain, exemplified by dishes like “Chiles en Nogada” (Chiles in Walnut Sauce), which pay homage to her interconnected roles as both a deity of fire and fertility. Chantico’s enduring presence thus enriches contemporary practices, seamlessly bridging the past and the present.

Related Images

Sources

Encyclopaedia Britannica. (n.d.). Aztec religion. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Aztec-religion

Miller, M. E., & Taube, K. (n.d.). Chantico. In The gods and symbols of ancient Mexico and the Maya. University of Texas Press. https://www.utpress.utexas.edu/books/milgod

Smithsonian National Museum of Asian Art. (n.d.). Codex Borgia. https://asia.si.edu/collection/codex-borgia/

World History Encyclopedia. (2021). Chantico. https://www.worldhistory.org/Chantico/

Miller, M. E., & Taube, K. (1993). An illustrated dictionary of the gods and symbols of ancient Mexico and the Maya. Thames & Hudson.

Sahagún, B. de. (2012). Florentine Codex: General history of the things of New Spain (A. J. O. Anderson & C. E. Dibble, Trans.). University of Utah Press. (Original work published 1577)

Townsend, R. F. (2000). The Aztecs. Thames & Hudson

Olivier, G. (2004). Chantico and the symbolism of fire in Aztec ritual and ideology. Ancient Mesoamerica, 15(2), 215–229. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0956536104040187

Frequently Asked Questions

Who is Chantico in Aztec belief?

Chantico is the Aztec goddess of hearth fire and the home, representing the sacred flame that sustained daily life. She governed warmth, cooking, protection, and domestic order, making her one of the most intimate deities in Aztec religious practice, present in every household rather than distant temples.

What does Chantico symbolize?

Chantico symbolizes the dual nature of fire as both nurturing and dangerous. She represents warmth, nourishment, creativity, and protection, while also embodying restraint, discipline, and the consequences that arise when sacred boundaries are ignored.

Why is Chantico associated with punishment?

Chantico is associated with punishment because her myth describes her transformation into a destructive force after sacred laws were broken. This reflects the Aztec belief that divine power responds directly to human behavior, rewarding respect while punishing excess and disobedience.

Was Chantico a household deity?

Yes, Chantico was deeply connected to domestic life and hearth rituals. Families honored her through the household fire, viewing her presence as essential for protection, prosperity, and the maintenance of spiritual balance within the home.

What lesson does Chantico’s myth teach today?

Chantico’s story teaches the importance of balance and disciplined power. It reminds modern audiences that forces which sustain life, such as passion, creativity, and ambition, must be respected and controlled, or they risk becoming destructive.