Mama Nina : Goddess of Fire

Listen

At a glance

| Description | |

|---|---|

| Origin | Inca Mythology |

| Classification | Gods |

| Family Members | Viracocha (Father) |

| Region | Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador, Chile |

| Associated With | Fire, Volcanoes |

Mama Nina

Introduction

Mama Nina holds a vital position in Incan mythology as the elemental embodiment of fire. As one of the revered deities within the Inca pantheon, she symbolizes the dual nature of fire: both as a life-giving and purifying force, and as a destructive, unpredictable energy. Her name, drawn from the Quechua word nina meaning “fire,” encapsulates the role she plays in the spiritual and natural realms. While less universally recognized than goddesses like Pachamama, Mama Nina’s influence remains deeply ingrained in the traditions, rituals, and beliefs that continue to be honored in Andean communities. She is not merely a deity of heat and flame but a manifestation of transformation itself—guiding the renewal of life through both metaphorical and literal combustion.

Physical Traits

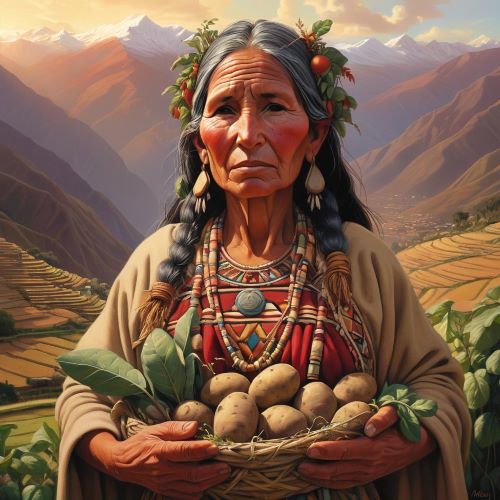

Although no standardized iconography of Mama Nina has survived due to the Inca’s preference for oral storytelling over written texts or visual representation, her attributes can be inferred through symbolic interpretations. As the goddess of fire and volcanoes, she is envisioned as radiant and awe-inspiring—an ethereal presence glowing with inner light, her body emanating the golden hues of flame. Some Andean oral traditions describe her as emerging from the mouths of volcanoes or dancing within ceremonial bonfires, emphasizing her inseparable link to both geological power and spiritual fervor. The heat and light of fire were seen as sacred gifts, and in every flicker of flame, the presence of Mama Nina was felt—watchful, fierce, and nurturing.

Family

In Incan cosmology, Mama Nina is one of the Cuatro Madres Elementales, or Four Elemental Mothers, along with Pachamama (Earth), Mama Qucha (Water), and Mama Wayra (Wind). These four deities were believed to collectively maintain the balance of nature and the cosmic order. They are often considered emanations or divine creations of Viracocha, the great creator god of the Inca. The relationship between these elemental goddesses wasn’t defined by human-like familial bonds but rather by their interconnected roles within the natural world. Mama Nina, as the fire aspect of this divine quartet, was invoked to bring energy, warmth, and purification. Her elemental sisters complemented her essence, working together in harmony to guide the cycles of life, agriculture, and human existence.

Other names

The name “Mama Nina” speaks directly to her elemental essence—“Mama” denoting maternal reverence and “Nina” referring to fire. Depending on regional dialects and cultural expressions, she is also known by several alternate names. Some traditions refer to her as Ñusta Nina, or “Princess of Fire,” reflecting her elevated spiritual status and her association with nobility. In more intense contexts—especially near volcanoes—she may be invoked as Mama Khuaco, or “Angry Fire,” acknowledging her capacity for destruction. Another poetic variation, Nina Mama, occasionally appears in chants or ritual songs, demonstrating the flexibility and richness of Quechua language in spiritual life. These diverse appellations all emphasize different facets of her power, whether maternal, regal, volatile, or sacred.

Powers and Abilities

Mama Nina’s dominion over fire granted her a wide array of spiritual and elemental powers. She was called upon to kindle flames in ceremonial rituals, ensuring the proper balance between humans and the divine. Fire under her guidance was seen not only as a tool for survival but as a means of spiritual purification—cleansing spaces, warding off evil, and transforming offerings into messages for the gods. Her presence was invoked in agricultural festivals, especially during the solstices, where the fire represented both the power of the sun and the beginning of new seasonal cycles.

Volcanoes, seen as sacred sites across the Andes, were considered her dwelling places. The eruptions and tremors associated with these geological giants were not feared as accidents of nature but honored as expressions of her will. When a volcano erupted, communities interpreted it as a sign of imbalance or divine communication, prompting offerings and rituals to appease her spirit. From igniting domestic hearths to orchestrating natural events of epic scale, Mama Nina’s power spanned every level of Andean life.

Modern Day Influence

Despite the fall of the Inca Empire, Mama Nina’s legacy continues to thrive in various forms across the Andean region. Fire remains central to many indigenous rituals today, particularly those related to healing, cleansing, and agricultural cycles. Ceremonial fires are still lit in the highlands of Peru and Bolivia, often accompanied by prayers and offerings aimed at maintaining harmony with the elemental spirits. In these rituals, the spirit of Mama Nina is ever-present, invoked silently in the glow of the flames.

Volcanoes continue to be seen as sacred sites, and in communities living near them, it’s not uncommon to make small offerings—such as coca leaves or maize beer—to ensure safety and balance. These practices are part of a broader resurgence of Andean spirituality, often referred to as Neo-Incan or Neo-Andean traditions, where practitioners reconnect with ancestral deities like Mama Nina to find strength, transformation, and healing in the modern world.

In artistic expressions, Mama Nina’s image has been reimagined in poetry, paintings, and folklore. She often appears as a powerful feminine figure who symbolizes inner fire and spiritual awakening. Her mythos has inspired contemporary artists and writers to explore themes of destruction and rebirth, drawing parallels with other fire deities from global traditions like Pele of Hawaii or the Celtic Brigid. Yet, Mama Nina’s connection to the Andes, to the sacred mountains and volcanic heart of South America, keeps her unique and deeply rooted in local belief systems.

Whether invoked during solstice ceremonies, commemorated through storytelling, or honored in modern art, Mama Nina remains a vibrant force in Andean culture. She embodies the potential within every spark—the capacity to destroy the old, illuminate the truth, and ignite the path to renewal.

Related Images

Source

Allen, C. J. (1988). The Hold Life Has: Coca and Cultural Identity in an Andean Community. Smithsonian Institution Press.

Bastien, J. W. (1985). Mountain of the Condor: Metaphor and Ritual in an Andean Ayllu. Waveland Press.

Dean, C. (2010). A Culture of Stone: Inka Perspectives on Rock. Duke University Press.

Salomon, F., & Urioste, J. (1991). The Huarochirí Manuscript: A Testament of Ancient and Colonial Andean Religion. University of Texas Press.

Contributors to WikiPagan. (n.d.). Mama Nina | WikiPagan – Fandom. https://pagan.fandom.com/wiki/Mama_Nina

Frequently Asked Questions

What is lorem Ipsum?

I am text block. Click edit button to change this text. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

What is lorem Ipsum?

I am text block. Click edit button to change this text. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

What is lorem Ipsum?

I am text block. Click edit button to change this text. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

What is lorem Ipsum?

I am text block. Click edit button to change this text. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

What is lorem Ipsum?

I am text block. Click edit button to change this text. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.