Azhdaya : The Three-Headed Dragon of Baltic Legends

Listen

At a glance

| Description | |

|---|---|

| Origin | Baltic Mythology |

| Classification | Animals |

| Family Members | N/A |

| Region | Poland, Serbia, Slovakia |

| Associated With | Dragons, Fire, Evil |

Azhdaya

Introduction

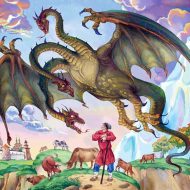

Azhdaya (also spelled Aždaja, Azhdaha, or Azdaha) is a legendary dragon-like creature found in the folklore of the Balkans and Slavic-speaking regions. Known for its terrifying strength and demonic nature, the Azhdaya is often described as the most fearsome of all Slavic dragons. Unlike benevolent or neutral dragons in some mythologies, the Azhdaya embodies chaos, destruction, and evil — a stark contrast to the heroic dragon-slayer traditions that emerged in Christianized Eastern Europe.

Etymologically, the term Aždaja derives from the Persian Aždahā (اژدها), meaning “dragon” or “serpent.” This linguistic borrowing likely entered the Slavic lexicon through centuries of cultural contact with the Ottoman Empire and Persian-influenced Islamic traditions. Over time, the creature’s image evolved from a symbol of raw elemental power into a representation of demonic evil — a shift influenced by the Christian reinterpretation of older pagan beliefs.

In Serbia, Bosnia, and Montenegro, Azhdaya is known as the monstrous adversary slain by Saint George (Sveti Đorđe), a motif that merges pre-Christian dragon myths with Christian saintly heroism. In this telling, the saint’s victory over the Azhdaya symbolizes the triumph of divine light over infernal darkness.

Physical Traits

The Azhdaya’s appearance varies across the Slavic regions, but its core traits remain consistent — a massive, serpentine body, thick scales, and an odd number of heads, often three, five, or seven. Each head could spew fire independently, and some stories describe it as so enormous that it could encircle mountains or block rivers with its body.

Older folk songs from Serbia and Bulgaria portray Azhdayas as ancient beings that once lived peacefully underground but became malevolent after centuries of isolation. Their roar was said to shake the earth, and their breath could scorch fields, dry rivers, and blacken the sky.

In Christian iconography, the Azhdaya’s form — particularly its many heads and fiery breath — became a visual shorthand for Satan and demonic forces. Frescoes and folk paintings often depict Saint George piercing an Azhdaya-like dragon beneath his horse’s hooves, emphasizing its role as the personification of evil.

Other Names

Throughout the Balkans and Eastern Europe, the Azhdaya appears under different names that reflect local linguistic traditions. In Serbian and Bosnian folklore, it is called Aždaja, in Bulgarian it is sometimes equated with Ala or Hala, and in Albanian oral tradition, a similar creature is referred to as Azdeha. Despite the variations, these names all share a linguistic root in the Persian Aždahā, revealing how ancient Near Eastern serpent mythology merged with Slavic cosmology.

Within the wider Slavic mythological system, dragons fall into several categories. The Zmaj or Zmey is often seen as an ambivalent being, capable of both protecting and destroying, while the Ala represents a storm demon associated with hail, drought, and unpredictable weather. The Azhdaya, however, is distinct for its purely destructive role. It exists only to consume, conquer, and corrupt. In Serbian epic poetry, the Azhdaya often emerges as the enemy of heroes, the ultimate test of courage and divine favor.

Powers and Abilities

The Azhdaya’s powers were vast and terrifying. It was said to fly across the skies, breathe fire hot enough to melt iron, and cause storms that tore through villages. It was often blamed for natural disasters, volcanic eruptions, and droughts, acting as a mythic explanation for forces beyond human control. The creature was also thought to dwell deep underground or within mountain caverns, where it guarded immense treasures or the entrances to other worlds. Only saints or divinely chosen heroes were capable of defeating such a beast, and its death was usually followed by signs of cosmic renewal, such as the return of rain or the end of famine.

In some oral traditions, Azhdayas could take human form, using deceit and transformation to infiltrate communities. Their shape-shifting ability and mastery of elemental forces positioned them as both physical and spiritual threats—representing not just external destruction, but moral and religious corruption as well. The Azhdaya’s hatred of light and holiness reinforced its role as a demonic counterpart to the divine order, a shadow cast against the moral fabric of the human world.

Modern Day Influence

The legend of the Azhdaya continues to influence Balkan culture, art, and language. In Serbian and Bosnian dialects, the word aždaja is still used colloquially to describe anything monstrous, greedy, or overwhelmingly powerful. Folk performances and songs celebrating Saint George’s victory over the dragon are still performed in parts of Serbia and Montenegro, keeping the ancient myth alive within the rhythms of modern faith and tradition.

Contemporary authors and artists draw upon the image of the Azhdaya as a symbol of primal fear and untamed nature. Its depiction has also found its way into modern fantasy media, inspiring multi-headed dragons and demonic monsters in books, films, and video games. Beyond entertainment, scholars continue to study the Azhdaya as an example of mythic adaptation—tracing how ancient Iranian and Indo-European serpent myths transformed into Christianized Balkan folklore. Through these reinterpretations, the Azhdaya endures not merely as a creature of myth, but as a cultural bridge connecting civilizations, religions, and centuries of storytelling.

Related Images

Sources

“Aždaha – European Muslim Dragons.” (2018, September 23). History & Culture. Retrieved from https://islam4europeans.com/2018/09/23/azdaha-european-muslim-dragons/

“Slavic dragon.” (n.d.). In Wikipedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Slavic_dragon

“AŽDAHĀ – Encyclopaedia Iranica.” (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/azdaha-dragon-various-kinds/

Saadi-nejad, M. (2023). Dragons, the Avestan saošiiant, and possible connections to Iranian dragon-lore. Hunara Journal. Retrieved from https://www.hunara.org/article_173300_b715bd6eb2d81ea6f32c1b103256554d.pdf

“Azhdaha.” (n.d.). In Myth and Folklore Wiki – Fandom. Retrieved from https://mythus.fandom.com/wiki/Azhdaha

“Azhdaha – Animals Wiki – Fandom.” (n.d.). Retrieved from https://animals-are-cool.fandom.com/wiki/Azhdaha

“Azhdaha – Dragon Discourse.” (n.d.). Retrieved from https://dragon-discourse.tumblr.com/post/646914130111086592/azhdaha

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a 3 headed dragon called?

The three headed dragon is known in different names. Three-headed monster may refer to: Azi dahaka, a three-headed dragon in Persian mythology. Cerberus, a multi-headed (usually three-headed) dog in Greek and Roman mythology. Zmiy Gorynych, a multi-headed (usually three-headed) Slavic dragon. King Ghidorah, a three-headed dragon in the Godzilla franchise.

What is the Russian name for dragon?

Zmei Gorynich or zmei in skazki (Russian folktales) and byliny (Russian epic poetry), is a dragon or serpent, or sometimes a human-like character with dragon-like traits.

What do dragons represent in Russia?

Some of the common motifs concerning Slavic dragons include their identification as masters of weather or water source; that they start life as snakes; and that both the male and female can be romantically involved with humans.

Are there dragons in Russian mythology?

In the legends of Russia and Ukraine, a particular dragon-like creature, Zmey Gorynych (Russian: Змей Горыныч or Ukrainian: Змій Горинич), has three to twelve heads, and Tugarin Zmeyevich (literally: “Tugarin Dragon-son”), known as zmei-bogatyr or “serpent hero”, is a man-like dragon who appears in Russian.