Wunggurr : The Serpent Ancestor of the Kimberley Landscapes

Listen

At a glance

| Description | |

|---|---|

| Origin | Ngarinyin Mythology |

| Classification | Animals |

| Family Members | N/A |

| Region | Australia |

| Associated With | Rains, Creation, Storms |

Wunggurr

Introduction

Wunggurr occupies a central place in the spiritual worldview of the Ngarinyin people of the northern Kimberley, forming one half of the important Wanjina–Wunggurr cosmological system. Unlike many Aboriginal Rainbow Serpent traditions found across Australia, the Wunggurr identity is deeply interwoven with Wandjina lore, creating a unique spiritual framework that governs creation, rainfall, land stewardship, and ceremonial obligation. Within this belief system, Wunggurr is not simply a mythic serpent of ancient times; it is a living ancestral presence tied to waterholes, underground channels, and the cycles that govern both ecological and cultural life. The Wanjina–Wunggurr cultural bloc—comprising the Ngarinyin, Worrorra, Wunambal, and Gaambera peoples—recognises Wunggurr as an embodiment of spiritual energy, creation force, and the continuity of ancestral law. Throughout generations, Wunggurr has guided sacred responsibilities, land care, and the transmission of knowledge, ensuring the inseparable bond between people, place, and story.

Physical Traits

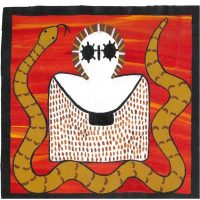

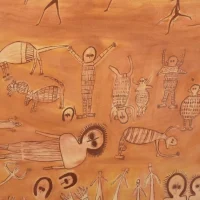

Descriptions of Wunggurr vary across communities, yet its essential form remains serpentine and immense, often conceptualised through the imagery of the Rainbow Serpent. Its body is associated with iridescent colours and glistening scales that echo the shimmering arc of a rainbow stretching between earth and sky. In many traditions, Wunggurr resides in deep waterholes and beneath riverbeds, and its movements are linked to storms, seasonal flooding, and the replenishment of freshwater systems crucial to the Kimberley landscape. Although Wandjina rock art is widely represented across the region, depictions of Wunggurr itself are rare; instead, its presence is implied through serpentine lines or the symbolic relationship between clouds, rain, and waterways. This subtle representation reflects its nature—felt, heard, and experienced through the environment rather than directly portrayed. The Rock Python, known in certain contexts as Wanjad or Ungud, is sometimes understood as one of Wunggurr’s earthly manifestations, reinforcing its connection to both the subterranean world and the life-giving forces that flow beneath the land.

Family

In the cosmological structure of the Ngarinyin and their neighbouring groups, Wunggurr is not organised into a conventional familial lineage but forms part of a spiritual kinship network shared across the Wanjina–Wunggurr cultural system. It holds ancestral ties to clans whose identities emerge from particular waterholes and sites associated with its presence. These locations are considered resting places of the serpent ancestor and serve as focal points for ceremonies and custodial obligations. Wunggurr’s closest spiritual relationships are with the Wandjina spirits, who govern clouds, rain, and the seasonal cycles. Together, the two forces represent the full spectrum of water—from the unseen subterranean channels of Wunggurr to the visible cloud and storm patterns of the Wandjina. This combined system of law shapes origin stories, cultural responsibilities, and the intergenerational transmission of sacred knowledge throughout the region.

Other names

The name Wunggurr is recorded with several variations depending on language group and orthographic style, including Wunngurr and Wunggurru. In some anthropological accounts, Wunggurr is associated with or identified as Ungud, a powerful serpent figure in related Kimberley traditions. Although sometimes broadly connected to the Rainbow Serpent motif found across the continent, the Kimberley interpretation is culturally distinct and tied to local landforms, water systems, and the deep-time stories shared by the Wanjina–Wunggurr peoples. References to Wunggurr frequently appear alongside Wandjina terminology, highlighting the interdependent relationship between the serpent of the deep and the rain-bearing sky spirits who formed the iconic Wandjina rock art tradition.

Powers and Abilities

Wunggurr’s abilities extend across creation, ecological balance, and the governance of spiritual law. As a creator ancestor, Wunggurr shaped the Kimberley environment by carving riverbeds, forming waterholes, and establishing the foundations of fertility across the region. Its control over water makes it central to the arrival of rain, the rise of floods, and the renewal of plant and animal life. The power associated with Wunggurr, known in some traditions as miriru or mururu, grants profound “clear vision,” enabling spiritual insight and the ability to access deeper layers of the Dreaming. Many Elders describe underground or underwater realms beneath Wunggurr-inhabited pools—mirrored worlds filled with kin, vegetation, and pathways to Dulugun, the land of the dead. Skilled dreamers, including composers and healers, are said to travel on the back of Wunggurr through these hidden spaces to receive songs, guidance, or healing power. This spiritual mobility reinforces Wunggurr’s role as a mediator between the material world, the ancestral plane, and the continuous flow of creative energy that sustains all living beings.

Modern Day Influence

Wunggurr remains a living spiritual force within contemporary Kimberley communities, where it continues to guide cultural identity, ceremony, and the stewardship of sacred sites. The Mowanjum Community, home to Ngarinyin, Worrorra, and Wunambal peoples, plays a major role in preserving the Wanjina–Wunggurr tradition through art centres, cultural festivals, and intergenerational teaching. Wandjina and serpentine motifs appear in contemporary artworks, which serve both as cultural expression and as an important medium for passing on law and story. Indigenous ranger programs throughout the Kimberley operate under principles drawn from Wunggurr’s ecological teachings, integrating traditional ecological knowledge with modern conservation practices to protect waterways, sacred pools, and biodiversity. Legally and politically, the Wanjina-Wunggurr Aboriginal Corporation stands as a guardian of native title rights and cultural heritage, formalising the unity of the cultural bloc and supporting communities in caring for country. Wunggurr’s continued presence in art, land management, and community initiatives ensures that the cosmology remains dynamic, relevant, and deeply rooted in everyday life. It stands as a symbol of endurance, resilience, and the unbroken thread of ancestral wisdom in one of the world’s oldest living cultures.

Related Images

Source

Redmond, B. (1995). The Wunggurr spirit in Ngarinyin dreaming. Journal of Australian Indigenous Studies, 3(2), 45-60.

Encyclopedia.com. (2025, October 15). Ungarinyin religion. Retrieved November 28, 2025, from https://www.encyclopedia.com/environment/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/ungarinyin-religion

Wunambal Gaambera Aboriginal Corporation. (2025). Wunambal Gaambera people and Wanjina Wunggurr connection. Retrieved November 28, 2025, from https://www.wunambalgaambera.org.au/about/wunambal-gaambera-people/

Intercontinental Cry. (2021, March 12). The Wanjina-Wungurr nation: Ancestral spirits of the Kimberley Indigenous peoples. Retrieved November 28, 2025, from https://icmagazine.org/indigenous-peoples/wanjina-wungurr/

University of Western Australia. (2022, November 22). Wanjina Wunggurr rock art and archival materials return to country from Germany after 80 years. Retrieved November 28, 2025, from https://www.crarm.uwa.edu.au/post/wanjina-wunggurr-rock-art-and-archival-materials-return-to-country-from-germany-after-80-years

Wunambal Gaambera Aboriginal Corporation. (n.d.). HCP final. Retrieved November 28, 2025, from https://www.wunambalgaambera.org.au/wp-content/uploads/HCP-final-e-version.pdf

Wanjina Wunggurr Traditional Owners. (n.d.). In Weltkulturen Museum. Retrieved November 28, 2025, from https://www.weltkulturenmuseum.de/en/research/guests/?guest=traditional-owners-nordwestaustralien-en

Elkin, A. P. (1930). Rock Paintings of North-West Australia. Oceania, 1(3), 257–279.

Radcliffe-Brown, A. R. (1926). The Rainbow Serpent Myth in Aboriginal Australia. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 56(2), 19–25.

Mowanjum Aboriginal Art & Culture Centre. (2025). Wanjina Wunggurr Traditions. Retrieved from https://www.mowanjumarts.com

Blundell, V., & Woolagoodja, D. (2005). Keeping the Wanjina Fresh: Cultural Revitalisation in the Kimberley. Fremantle Arts Centre Press.

Crawford, I. M. (1968). The Art of the Wandjina: Aboriginal Cave Paintings in Kimberley, Western Australia. Oxford University Press.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is Wunggurr in Aboriginal mythology?

Wunggurr is a powerful serpent ancestor in the Wanjina-Wunggurr cosmology of the Kimberley, associated with creation, water, and Dreaming.

Is Wunggurr the same as the Rainbow Serpent?

Wunggurr shares similarities with the Rainbow Serpent but is culturally distinct, forming a unique dual system with the Wandjina spirits.

Where does Wunggurr live according to tradition?

It is believed to reside in deep waterholes, underground channels, and sacred pools across the Kimberley region.

What powers does Wunggurr have?

Wunggurr controls water, rain, fertility, Dreaming travel, and spiritual insight known as “clear vision.”

How is Wunggurr represented today?

It remains central to cultural identity, appearing in art, ceremonies, and Indigenous ranger programs dedicated to land and water stewardship.