Exploring Diyu: Hell, Karma, and Reincarnation in Chinese Mythology

Diyu, often translated as the “Chinese underworld” or “hell,” is a realm of punishment and purification in Chinese mythology and religious tradition. Rooted in a combination of Buddhist, Taoist, and indigenous Chinese beliefs, Diyu is not merely a place of torment—it is a complex, multi-layered judicial system that reflects moral and ethical values deeply ingrained in Chinese culture. Unlike Western concepts of eternal damnation, Diyu offers the possibility of redemption and rebirth, making it a unique depiction of the afterlife.

Origins and Cultural Context

The concept of Diyu draws heavily from both Buddhist Naraka and Taoist cosmology, blended with traditional Chinese ancestor worship and ghost lore. As Buddhism spread to China during the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE), it merged with local beliefs to form a syncretic vision of the afterlife. This vision became popular through texts such as the Jade Record and folk stories recited during Hungry Ghost Festivals and Taoist rituals.

Diyu is presided over by Yama (Yanluo Wang), the King of Hell, who judges the souls of the dead. Supporting him is a complex bureaucracy of deities, judges, and demons who manage the soul’s journey, assign punishments, and determine the path to reincarnation.

Structure of Diyu

Diyu is often described as consisting of ten courts and eighteen levels, though variations in regional stories may include more. Each court is overseen by a Yan King (Yama King), and each level corresponds to a different type of sin, such as theft, deceit, or disrespect to elders.

For example:

-

The First Court deals with preliminary judgment.

-

The Fifth Court might handle liars and fraudsters.

-

The Eighteenth Level is reserved for the most heinous crimes, such as mass murder or betrayal of one’s own family.

Punishments in Diyu are imaginative and symbolic. Sinners may be boiled in oil, ground by wheels, or forced to climb mountain blades, but these torments are not eternal. The goal is atonement and purification, preparing the soul for its next life.

Role of Karma and Reincarnation

In the Diyu belief system, karma (yin guo bao ying) is paramount. Actions in life—whether virtuous or wicked—determine one’s fate after death. If a person has committed more good deeds, they may avoid Diyu altogether or face only mild judgments. Conversely, those with a heavy karmic burden are subjected to the full scope of its horrors.

After enduring punishment, the soul drinks the “Meng Po Soup”, a brew that erases all memory of previous lives, before being reincarnated. This cycle emphasizes the impermanence of both suffering and identity, aligning with Buddhist ideas of rebirth and transformation.

Symbolism and Influence

Diyu is more than just a mythological space—it serves as a moral compass for the living. It instills values such as filial piety, honesty, and respect for social order. Parents and elders often reference Diyu as a deterrent, warning of the dire consequences of immoral behavior.

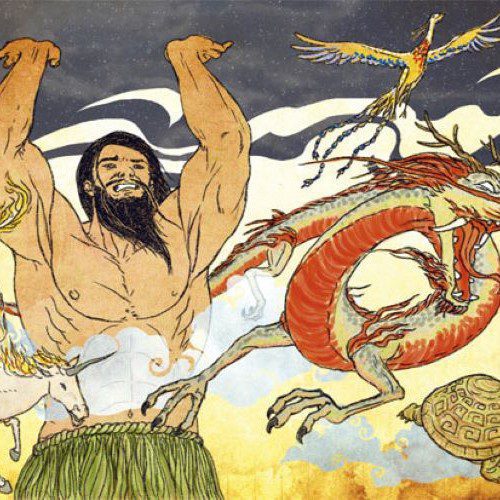

This underworld has also been a rich source of inspiration for Chinese opera, literature, and art. Paintings of Diyu often depict ghastly demons, tortured souls, and complex bureaucracies, reflecting societal fears and spiritual beliefs. One of the most famous examples is the Ten Kings of Hell murals found in ancient temples.

Diyu in Modern Culture

Even in the modern era, the imagery of Diyu continues to captivate. It appears in films, television dramas, manhua (Chinese comics), and even video games. Horror and fantasy genres particularly draw from the terrifying yet structured portrayal of the afterlife in Chinese tradition. Titles like Painted Skin and The Ferryman: Legends of Nanyang explore themes rooted in Diyu lore.

Furthermore, the continued celebration of the Ghost Month, when spirits are believed to return from Diyu to visit the living, shows that these beliefs still resonate with Chinese communities around the world.

No posts were found.