Ruaumoko : God of Earthquakes

Listen

At a glance

| Description | |

|---|---|

| Origin | Maori Mythology |

| Classification | Gods |

| Family Members | Papatūānuku (Mother), Ranginui (Father), Tāne-mahuta, Tangaroa, Tūmatauenga, Rongo, Haumia-tiketike, Tāwhirimātea (Siblings) |

| Region | New Zealand |

| Associated With | Earthquakes, Volcanoes |

Ruaumoko

Introduction

Ruaumoko, a formidable presence in Māori mythology, represents the raw, untamed power of the natural world. Revered as the god of earthquakes, volcanoes, and the changing seasons, he is a critical figure in the cosmological narrative of Aotearoa (New Zealand). As the youngest child of Rangi (Sky Father) and Papa (Earth Mother), Ruaumoko was never born in the conventional sense. Instead, he remains within the womb of his mother, deep beneath the earth’s surface. His stirrings are believed to cause earthquakes and volcanic eruptions, making him both feared and respected among the Māori. Unlike many deities who dwell in the sky or the oceans, Ruaumoko’s dominion lies in the unseen, in the trembling core of the planet. His myth explains not only geological phenomena but also connects spiritual belief with the land and its volatile nature.

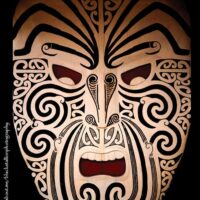

Physical Traits

Traditional Māori narratives often focus more on symbolic representation than detailed physical descriptions of their deities. Ruaumoko is no exception. His form is rarely, if ever, illustrated in historical sources, suggesting that his identity is better understood through the forces he commands than through any physical depiction. The lack of visual portrayal may itself be symbolic—his domain is underground, unseen, and powerful, evoking mystery and awe. When Ruaumoko is personified in storytelling, he is sometimes imagined as a restless child in the womb of Papa, his unease manifesting as tremors and lava flows. This poetic interpretation reflects the Māori way of embodying natural forces in human-like beings, emphasizing relationships over appearances.

Family

Ruaumoko’s lineage roots him in the very origin of the cosmos according to Māori belief. He is the youngest of the numerous children of Rangi and Papa. These divine parents once embraced so tightly that their children were trapped in darkness. As his siblings—who include Tāne (god of forests), Tangaroa (god of the sea), and Tūmatauenga (god of war)—forced their parents apart to let light into the world, Ruaumoko remained within Papa. His refusal, or perhaps inability, to emerge created a permanent link between him and the subterranean world. He became the guardian of geothermal and seismic forces. Unlike his brothers who took dominion over parts of the world above, Ruaumoko’s role was to remain in the earth’s belly, stirring the land and shifting its very bones. His familial placement helps explain his emotional connection to the earth and his immense, unpredictable power.

Other names

Ruaumoko’s identity is preserved through a variety of names across Polynesian cultures, each emphasizing a different aspect of his mythos. In Aotearoa, the name “Ruaumoko” translates directly to the idea of subterranean rumbling—rua meaning pit or cave, and umoko possibly linked to internal heat or fire. In Tahitian mythology, variations of his name such as “Ru the Transplanter” and “Ru the Great Valiant One” reflect his broader significance as a figure of strength and cosmic change. Another Polynesian variant, “Ru-te-toko-rangi,” speaks of a being who played a part in raising the sky—a reference to another foundational myth about the separation of earth and sky. These different names and roles suggest that Ruaumoko was not only a god of destruction but also of transformation, helping shape the world through force and upheaval.

Powers and Abilities

Ruaumoko’s powers are as vast and formidable as the forces of nature themselves. His most prominent ability lies in causing earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. As he moves within the earth’s depths, his motions send shockwaves to the surface, shaking mountains, boiling lakes, and triggering eruptions. His breath is said to be the heat that fuels volcanic activity, while his movements result in tectonic shifts. In some seasonal traditions, Ruaumoko is also linked to the transition between summer and winter. As he stirs beneath the surface, he brings cold from the underground during the winter months and warmth as he quiets down in summer. This makes him a deity not only of sudden chaos but also of cyclic renewal. In other Polynesian cultures, Ru is regarded as a voyager and explorer, a leader who charted lands and raised the heavens. This duality of power—both geological and cultural—marks him as a multi-dimensional figure in the mythological landscape.

Modern Day Influence

Despite centuries of colonial suppression, Ruaumoko continues to resonate deeply within modern Māori identity. Today, his presence is acknowledged not just in oral tradition but in literature, art, and education. Ruaumoko is often evoked in discussions about the land—especially in relation to seismic activity in New Zealand, one of the most geologically active regions on Earth. His myth offers a cultural lens through which natural disasters are interpreted, transforming fear into understanding and reverence. In the world of contemporary Māori art, Ruaumoko appears as a symbol of both creation and destruction. Writers and artists use his story to reflect themes of resistance, survival, and adaptation. He is also found in school curricula and public storytelling, helping new generations connect to their heritage.

Furthermore, Ruaumoko’s mythology intersects with global scholarly exploration of ancient symbolic systems. His story is now being studied alongside other ancient myths from Egypt, Turkey, India, and China, revealing striking thematic similarities. This comparative approach is reshaping how people view Māori cosmology—not as an isolated tradition, but as part of a wider, perhaps even primordial, understanding of the world and its forces. These connections have led some researchers to argue that Māori ancestors possessed advanced knowledge of astronomy, navigation, and geological phenomena that rival ancient civilizations.

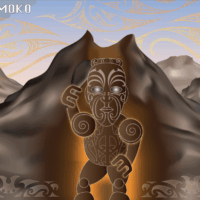

Related Images

Source

Best, E. (1924). The Maori. Wellington: Harry H. Tombs. Retrieved from https://pantheon.org/articles/r/ru.html

McSaveney, E. (2009). Historic earthquakes – Earthquakes in Māori tradition. Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved from https://teara.govt.nz/en/1966/maori-myths-and-traditions

Te Papa. (2012). Ruaumoko – God of Earthquakes. Earthquake Commission. Retrieved from https://eng.mataurangamaori.tki.org.nz/Support-materials/Te-Reo-Maori/Maori-Myths-Legends-and-Contemporary-Stories

Tregear, E. (1891). Maori-Polynesian Comparative Dictionary. Wellington: Government Printer. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/maorireligionmyt00shor

White, J. (1887). Ancient History of the Maori. Wellington: Government Printer. Retrieved from https://ngaitahu.maori.nz/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/The-Mythology-and-Traditions-of-the-Maori-in-New-Zealand-Wholers.pdf

Frequently Asked Questions

What is lorem Ipsum?

I am text block. Click edit button to change this text. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

What is lorem Ipsum?

I am text block. Click edit button to change this text. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

What is lorem Ipsum?

I am text block. Click edit button to change this text. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

What is lorem Ipsum?

I am text block. Click edit button to change this text. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

What is lorem Ipsum?

I am text block. Click edit button to change this text. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.