Petsuchos : The Sacred Crocodile

Listen

At a glance

| Description | |

|---|---|

| Origin | Egyptian Mythology |

| Classification | Animals |

| Family Members | N/A |

| Region | Egypt |

| Associated With | Guardian, Protection |

Petsuchos

Introduction

In the world of ancient Egyptian mythology, few sacred beings capture the imagination quite like Petsuchos, the living crocodile worshipped as the earthly manifestation of the god Sobek. Revered in the city of Crocodilopolis (modern-day Faiyum), Petsuchos symbolized divine strength, fertility, and protection. The name itself derives from the Greek Πετεσοῦχος (Petesuchos), meaning “son of Suchos,” with Suchos being the Greek name for Sobek. To the ancient Egyptians, this crocodile was not merely an animal but a living god, cared for by temple priests, adorned with gold and jewels, and believed to embody the very essence of Sobek’s power. The worship of Petsuchos reflected Egypt’s profound respect for nature and its belief in the harmony between the mortal and divine worlds.

Physical Traits

Physically, Petsuchos was a living Nile crocodile, majestic and terrifying in equal measure. Ancient texts and Greek historians like Herodotus describe how the sacred crocodile was raised in temple lakes near Faiyum. These animals were lavishly decorated with golden ornaments, precious stones, and amulets, particularly around their heads, necks, and feet. The adornments were not mere decoration—they were sacred symbols, marking Petsuchos as a divine incarnation rather than an ordinary beast.

Priests attended to the crocodile’s every need, feeding it carefully chosen food, often from the hands of the devout. Visitors to Crocodilopolis brought offerings and paid homage to this living deity. The creature’s smooth, glistening scales were said to catch the sunlight, giving it an otherworldly glow that symbolized Sobek’s radiance. It lived in specially constructed pools within temple complexes, sometimes accompanied by other crocodiles, though only one was recognized as the true Petsuchos at a time. When the sacred crocodile died, it was mummified with great ceremony and replaced by another chosen specimen, ensuring the uninterrupted presence of Sobek’s spirit on earth.

Family

In Egyptian theology, Petsuchos did not belong to a biological family but to a divine lineage. It was believed to be the direct earthly embodiment of Sobek, who himself was a prominent deity connected to the Nile River, fertility, and military might. Sobek’s parentage varies across traditions: in some myths, he was born from the primordial waters of Nun, while in others, he was the son of Neith, the goddess of creation and war. Petsuchos, therefore, represented Sobek’s continued presence among mortals—his ka or life force manifest in living form.

The title “son of Suchos” emphasizes this relationship. Each new Petsuchos was ritually consecrated to carry Sobek’s divine energy, much like how Egyptian kings were believed to inherit the spirit of Horus. This cyclical process of death, mummification, and rebirth symbolized the eternal nature of divine power, reinforcing Sobek’s protective role over the Nile and its people.

Other names

The sacred crocodile was known by several names depending on time and region. The most common form, Petsuchos or Petesuchos, is derived from Greek, meaning “offspring of Sobek.” Egyptian inscriptions sometimes referred to it simply as “the Living Sobek” or “Sobek on Earth.” In temples influenced by solar cults, such as those blending the worship of Sobek and Ra, Petsuchos was occasionally called Petsuchos-Ra, highlighting its association with the sun god and its perceived radiance and vitality.

In Ptolemaic and Roman Egypt, the name “Suchos” was frequently used to refer to Sobek himself, and Greek visitors often referred to the sacred crocodile with reverence, recognizing it as both a divine animal and a cultural emblem of Egypt’s spiritual sophistication. The interchangeability of these names demonstrates how Greek and Egyptian religious ideas merged during this period, creating a hybrid tradition that preserved Petsuchos’s sacred identity for centuries.

Powers and Abilities

As the embodiment of Sobek, Petsuchos was believed to possess immense supernatural power. Ancient Egyptians attributed to it the same divine attributes as Sobek—strength, fertility, protection, and dominion over the Nile’s waters. Worshippers believed Petsuchos could control the river’s flooding, ensuring fertile crops and prosperity. Its presence was also said to ward off evil spirits and protect devotees from misfortune.

Mythologically, Sobek—and therefore Petsuchos—was associated with solar and military power. The sacred crocodile was thought to channel energy from the sun, symbolized by the golden ornaments adorning its body. Some depictions include a solar disc atop a bull-horned headdress, linking Sobek to Ra and emphasizing Petsuchos’s role as a radiant force of creation and destruction. The creature’s duality mirrored the Nile itself: life-giving in abundance, deadly in excess.

Priests also claimed that Petsuchos had an aura of divine presence, capable of inspiring awe and fear. To stand before the sacred crocodile was to be in the presence of Sobek himself. Offerings made to Petsuchos were believed to bring blessings, healing, and fertility, and failure to show proper respect could invite divine retribution. When Petsuchos died, it was mummified and entombed with ritual offerings, as befitted a god, before another chosen crocodile assumed the sacred role.

Modern Day Influence

Though the cult of Petsuchos faded with the fall of ancient Egyptian religion, its legacy remains remarkably enduring. Archaeological excavations in Faiyum, Kom Ombo, and Esna have unearthed hundreds of mummified crocodiles, many adorned with linen wrappings and amulets, confirming the scale and devotion of Sobek’s worship. These discoveries provide direct insight into Egypt’s unique practice of animal deification, where divine power could inhabit living creatures.

Today, Petsuchos and Sobek are subjects of fascination for Egyptologists, historians, and the general public alike. Museums such as the British Museum, the Louvre, and the Cairo Museum feature crocodile mummies and inscriptions referencing the sacred Petsuchos. In modern media, the myth survives through films, video games, and literature exploring Egyptian mythology—titles like Assassin’s Creed: Origins and fantasy novels reimagine Petsuchos as a divine guardian or powerful beast.

Beyond pop culture, the symbolism of Petsuchos continues to resonate. Its representation of balance between creation and destruction, strength and serenity, mirrors humanity’s relationship with nature. Scholars studying Egypt’s religious ecology often cite Petsuchos as a powerful example of how ancient societies viewed the animal world as a direct extension of the divine realm.

In modern spiritual and artistic interpretations, Sobek and Petsuchos are invoked as emblems of courage, protection, and renewal—qualities still admired in a world that continues to draw inspiration from Egypt’s timeless myths.

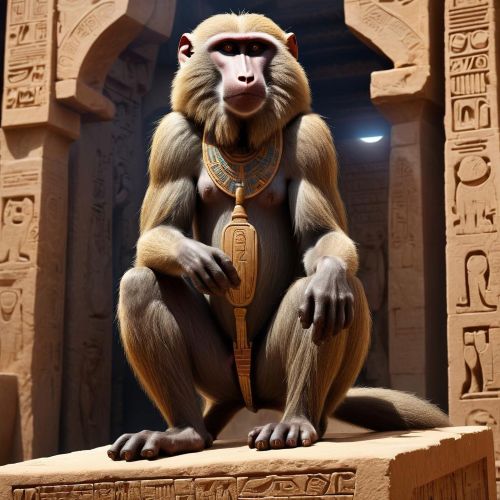

Related Images

Source

Monstropedia. (n.d.). Petsuchos. Retrieved October 31, 2025, from https://www.monstropedia.org/index.php?title=Petsuchos

Mythology Vault. (n.d.). Sobek Crocodile God Power. Retrieved October 31, 2025, from https://mythologyvault.com/mythologies-by-culture/egyptian-mythology/sobek-crocodile-god-power/

Maverick Werewolf. (2024, September 27). Mythology Fact #1 – Sobek, Egyptian Crocodile God. Retrieved October 31, 2025, from https://maverickwerewolf.com/mythology-fact-1-sobek-egyptian-crocodile-god/

Cult of Sobek. (2023, August). Exclusive Interview: Cult of Sobek talk “Petsuchos”! Metal Noise. Retrieved October 31, 2025, from https://metalnoise.net/2023/08/exclusive-interview-cult-of-sobek-talk-petsuchos

GMBinder. (n.d.). Petsuchos. Retrieved October 31, 2025, from https://www.gmbinder.com/share/-LQ6OYyKd2WbqlvwP9t-/-LQ6mroBSuS_w8sM7JpW

Warriors of Myth Wiki. (n.d.). Petesuchos. https://warriorsofmyth.fandom.com/wiki/Petesuchos

Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2023). Sebek Crocodile God, Nile River & Ancient Egypt. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Sebek

Dunand, F., & Zivie-Coche, C. (2004). Gods and Men in Egypt: 3000 BCE to 395 CE. Cornell University Press.

Wilkinson, R. H. (2003). The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson.

Pinch, G. (2002). Egyptian Myth: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press.

David, R. (1998). Handbook to Life in Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press.

Bleeker, C. J. (1967). The Egyptian Religion. Brill Academic Publishers.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is lorem Ipsum?

I am text block. Click edit button to change this text. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

What is lorem Ipsum?

I am text block. Click edit button to change this text. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

What is lorem Ipsum?

I am text block. Click edit button to change this text. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

What is lorem Ipsum?

I am text block. Click edit button to change this text. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

What is lorem Ipsum?

I am text block. Click edit button to change this text. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.