Izanagi: The Divine Creator Who Shaped the Japanese Islands

Listen

At a glance

| Description | |

|---|---|

| Origin | Japanese Mythology |

| Classification | Gods |

| Family Members | Izanami (Wife), Amaterasu (Daughter) |

| Region | Japan |

| Associated With | Creation, Land of Dead |

Izanagi

Introduction

Izanagi and Izanami hold pivotal roles in Japanese mythology, particularly Izanagi, who embodies creation, life, and the cycle of death and rebirth. Among Japan’s rich pantheon of deities, Izanagi is revered as a prominent figure, embodying the essence of creation in Shinto mythology. His narrative revolves around themes of creation, family, and the delicate balance between life and death. Through exploring Izanagi’s mythology, we uncover his distinctive physical traits, familial connections, divine powers, and enduring influence on modern Japanese culture. Credited with the creation of Japan alongside Izanami, Izanagi is hailed as a significant creator deity, fathering numerous kami or gods. His pivotal role in shaping the world and his myriad adventures remain central to Japanese mythology.

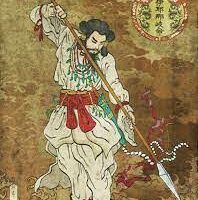

Physical Traits

Depictions of Izanagi vary, but he is commonly portrayed as a handsome and powerful male figure. Some representations showcase him wielding the Ame-no-Nuboko, a heavenly jeweled spear, symbolizing his involvement in churning the primordial seas. Typically, Izanagi is depicted as a noble and robust figure, embodying masculinity and vitality with his regal presence and long, flowing hair. Adorned in traditional Japanese attire, he signifies his divine status. The Ame-no-Nuboko, or “Heavenly Jeweled Spear,” is a prominent feature in his iconography, representing his authority and role in the creation of Japan. Although specific physical attributes are sparse in the myths, Izanagi is consistently depicted as a powerful force of creation and life.

Family

Izanagi and Izanami, the first of the Kamiyonanayo, initiated the procreation of the Japanese islands and the kami. Izanagi, notably, fathered Amaterasu, the sun goddess and leader of heaven, establishing a lineage connecting him to the Japanese Imperial family. Their union is symbolized by the moniker “The Eight-Forked Serpent,” signifying the celestial and terrestrial realms merging. Tasked by primordial gods to create the world, their union birthed deities like Amaterasu and Tsukuyomi. Tragedy struck when Izanami died birthing Kagutsuchi, the fire god. Grieving, Izanagi journeyed to the underworld in vain attempts to revive her, ultimately returning alone. Their lineage, spanning from the seventh generation of primordial deities, reflects the ancient state of existence, where familial distinctions were less defined. Through their divine union, Izanagi and Izanami became ancestors to a multitude of kami, including Amaterasu, Tsukuyomi, and Susanoo, who further shaped the cosmos.

Other names

Throughout history, Izanagi has been known by various names and titles, reflecting his multifaceted nature and significance in Japanese mythology. In addition to his primary name, he is referred to as “The Male Who Invites” or “The Male Who Invites Birth,” emphasizing his role as a creator and progenitor of life. Some interpretations also associate him with the title of “The Lord of the Sky,” emphasizing his authority over the celestial realm. Regardless of the name he bears, Izanagi remains a central figure in Japanese folklore and religious tradition. His name, “Izanagi,” derives from “iza,” meaning “invite” or “entice,” and “nagi,” meaning “male,” underscoring his role as an initiator of creation. He is also honored with the title “Izanagi-no-Mikoto,” signifying his role as the one who initiates creation. Additionally, he is known by other names such as “Izanagi-no-okami” or simply “Izanagi-no-Mikoto,” all of which emphasize his role as the one who invites or initiates.

Powers and Abilities

As a creator deity, Izanagi possesses a diverse range of powers and abilities, reflective of his pivotal role in shaping the world. Among his notable abilities is mastery over the elements, particularly water and fire. In Japanese mythology, Izanagi is credited with utilizing his powers to form the Japanese islands by stirring the ocean with his spear. Additionally, he holds dominion over life and death, evident in his journey to the underworld in search of Izanami. Although he couldn’t rescue her, Izanagi’s courage and determination amidst adversity underscore his divine strength and resilience.

Izanagi’s powers as a creator god are extensive. Alongside Izanami, he forged the Japanese islands and holds sway over Yomi, the Land of the Dead. His creative prowess extends to fathering numerous kami, embodying the essence of life. Notably:

Creation: Izanagi’s myth highlights his ability to create, illustrated when he churned the chaotic seas with the Ame-no-Nuboko, birthing the first island of Onogoro. Collaborating with Izanami, they brought forth the Japanese archipelago and myriad kami.

Purification: Following his encounter with the death-tainted Izanami in Yomi, Izanagi performs a purification ritual, cleansing himself in the sea, establishing the foundation for the Shinto purification practice of “harai.”

Life and Death: Izanami’s death during childbirth introduces the concepts of life and death. Izanagi’s journey to Yomi further solidifies this link, shaping the fundamental cycle of existence.

A significant tale recounts Izanagi’s descent into Yomi in a desperate bid to retrieve his deceased wife. Consumed by grief, he encounters Izanami, now a decaying and monstrous figure. Fleeing in terror, Izanagi seals the entrance to Yomi, separating the realms of the living and dead. This exchange between them establishes the enduring cycle of life and death.

Modern Day Influence

Japanese mythology, despite its ancient origins, maintains a profound influence on contemporary culture. Izanagi, in particular, holds a revered status in Japanese society, evidenced by the numerous shrines and festivals dedicated to his worship. His enduring legacy serves as a guiding light for many, imparting lessons of resilience, ingenuity, and the perpetual cycle of existence.

Furthermore, Izanagi’s profound impact extends beyond religious observance, permeating various facets of modern Japanese life. His story continues to inspire artistic expression, from traditional forms like painting and sculpture to contemporary mediums such as literature and cinema. Moreover, his timeless appeal resonates in popular culture and entertainment, where adaptations of his mythos captivate audiences worldwide.

In essence, Izanagi’s narrative transcends the boundaries of time and space, perpetuating a legacy that resonates across generations. As a symbol of perseverance and creativity, he reminds us of the enduring truths embedded within Japanese mythology and the intrinsic connection between past, present, and future.

Related Images

Sources

Breen, J., & Teeuwen, M. (2010). A new history of Shinto. Wiley-Blackwell.

Chamberlain, B. H. (Trans.). (1882). The Kojiki: Records of ancient matters. Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan.

Heldt, G. (Trans.). (2014). The Kojiki: An account of ancient matters. Columbia University Press.

Nelson, J. K. (2000). Enduring identities: The guise of Shinto in contemporary Japan. University of Hawai‘i Press.

Philippi, D. L. (Trans.). (1969). Kojiki. University of Tokyo Press.

Reider, N. (2018). Japanese mythology in film: A semiotic approach to reading Japanese culture. Lexington Books.

Teeuwen, M., & Breen, J. (2010). A new history of Shinto. Wiley-Blackwell.

Agency for Cultural Affairs of Japan. (n.d.). Izanagi Jingū. Cultural Heritage Online. https://bunka.nii.ac.jp/heritages

Awajishima Onokoro Shrine. (n.d.). The birthplace of Japan. Retrieved from https://www.onokorojinja.jp

Kokugakuin University. (n.d.). Japanese mythology database. https://k-amc.kokugakuin.ac.jp/DM/dbTop.do

Encyclopaedia Britannica. (n.d.). Izanagi (Japanese deity). In Encyclopaedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Izanagi

Mark, J. J. (2022, October 17). Izanagi. World History Encyclopedia. https://www.worldhistory.org/Izanagi/

Shinto Online Network Association. (n.d.). Misogi: Purification and the legacy of Izanagi. https://www.shinto.or.jp/

Frequently Asked Questions

Who is Izanagi in Japanese mythology?

Izanagi is one of the primary creator deities in Japanese mythology and Shinto belief. Alongside his consort Izanami, he formed the Japanese islands and gave birth to many of the kami, or gods. Known as “The Male Who Invites,” Izanagi symbolizes creation, purification, and the balance between life and death. His actions shaped the world and introduced sacred rituals that remain part of Japanese tradition today.

What did Izanagi and Izanami create?

Izanagi and Izanami are credited with creating the islands of Japan and the pantheon of Shinto deities. Using the sacred spear Ame-no-Nuboko, they stirred the primordial ocean to form the first island, Onogoro. Their union then produced the eight main islands of Japan and many gods, including Amaterasu (sun goddess), Tsukuyomi (moon god), and Susanoo (storm god).

What is the story of Izanagi and the underworld?

After Izanami died giving birth to the fire god Kagutsuchi, Izanagi journeyed to Yomi, the underworld, to bring her back. However, he found her transformed into a decaying spirit of death. Horrified, Izanagi fled and sealed the entrance to Yomi, separating the realms of the living and the dead. This myth explains the origin of mortality and the eternal cycle of life and death in Japanese cosmology.

What are Izanagi’s main symbols and powers?

Izanagi is associated with creation, purification, and renewal. His main symbol is the Ame-no-Nuboko, the heavenly jeweled spear used to shape the earth. He also represents purification through his “misogi” ritual—performed after returning from the underworld—which gave birth to new gods and established the foundation for Shinto cleansing ceremonies.

How is Izanagi worshipped in Japan today?

Izanagi continues to be venerated at several Shinto shrines, most notably the Izanagi Jingū on Awaji Island, believed to be the first land he and Izanami created. His legacy influences purification rituals, festivals, and artistic depictions across Japan. Modern worship emphasizes his role as a divine creator and protector, symbolizing harmony between the natural and spiritual worlds.