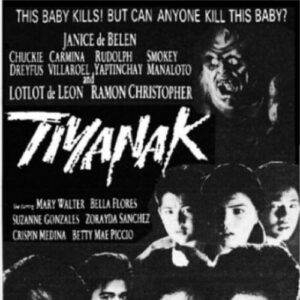

Tiyanak (1988)

| Description | |

|---|---|

| Country of Origin | Philippines |

| Language | Tagalog |

| Genre | Horror |

| Cast | Janice de Belen, Lotlot de Leon, Ramon Christopher, Mary Walter, Chuckie Dreyfus |

| Directed by | Peque Gallaga, Lorenzo A. Reyes |

Peque Gallaga and Lore Reyes’ Tiyanak (1988) stands as one of the most culturally significant horror films in Philippine cinema. More than a straightforward tale of terror, it is a chilling exploration of Filipino mythology, religious guilt, and the deep-seated fears that linger in rural communities. By turning the mythical tiyanak into a terrifying screen presence, the filmmakers breathe new life into an ancient legend, making it both relevant and unforgettable.

The film centers around Julie, played by Janice de Belen, a young woman recovering from personal trauma who decides to take in an abandoned infant. What begins as a compassionate act slowly unravels into a horrifying ordeal as the baby reveals itself to be a tiyanak—a demonic, shape-shifting creature that uses its infantile appearance and cry to lure victims. The transition from helpless newborn to bloodthirsty monster is handled with disturbing precision, creating a sense of dread that creeps in steadily and refuses to let go.

In Philippine mythology, the tiyanak is one of the most horrifying and tragic figures. Traditionally believed to be the spirit of an unbaptized or aborted baby, the tiyanak is cursed to remain in limbo and turns into a malevolent entity. It mimics the cries of a baby to attract passersby, only to attack them viciously when they come near. This myth reflects not just fear of the unknown but also societal anxieties surrounding issues like abortion, infanticide, and maternal responsibility—particularly within the framework of Catholicism, which has strongly influenced Filipino culture.

The film does not merely use the tiyanak as a gimmick; it engages with the creature’s deeper mythological meaning. Julie’s character is symbolic of modern womanhood—traumatized, navigating expectations of care and compassion, and ultimately blamed for circumstances beyond her control. Her initial desire to nurture and protect is manipulated by the tiyanak, which weaponizes maternal instinct. This mirrors how folklore can act as a moral compass, warning against certain actions and reinforcing societal norms, often at the expense of women’s autonomy.

Set in a rural village, Tiyanak is steeped in atmosphere. The environment is claustrophobic and eerie, with superstitious villagers, candle-lit churches, and ominous jungle surroundings contributing to the sense of isolation. The film cleverly contrasts Catholic imagery—holy water, rosaries, baptisms—with the pagan undertones of the tiyanak myth. The creature exists in a space outside salvation, a child that cannot be blessed or protected by religion, embodying spiritual unrest and unresolved guilt. This creates a profound tension between faith and folklore, tradition and terror.

The horror in Tiyanak is both physical and psychological. While the creature’s attacks are gruesome and visceral, the true terror lies in its symbolism. It represents the consequences of societal neglect, spiritual abandonment, and repressed trauma. The film doesn’t just show a monster; it reveals the cultural conditions that birthed it. In this sense, the tiyanak is not just a predator but a product—of lost souls, of sins unspoken, of children forgotten.

The filmmakers’ use of practical effects and makeup, while modest by today’s standards, adds to the rawness of the experience. The tiyanak’s transformation scenes are unsettling, maintaining just enough human characteristics to make its inhumanity more horrifying. The childlike wails that turn into guttural growls serve as a disturbing metaphor for innocence turned into rage.

What sets Tiyanak apart from many other horror films is its emotional depth. The creature is horrifying, yes, but it is also tragic. It is not evil for evil’s sake; it is a reflection of pain and rejection. This complex portrayal elevates the tiyanak beyond a standard movie monster and allows it to embody a uniquely Filipino fear—one that blends myth, morality, and the supernatural.

The film also plays a role in preserving and reintroducing Philippine folklore to modern audiences. By visualizing the tiyanak for the screen, it immortalizes a story once told only in hushed voices and fireside whispers. For many Filipinos, Tiyanak was the first time they “saw” the myth, and that image has stayed in the cultural psyche ever since. In a way, the film ensures the tiyanak continues to haunt both dreams and discussions long after the credits roll.

More than thirty years after its release, Tiyanak remains a landmark in horror cinema. Its success lies not only in scaring audiences but in rooting that fear in something deeply familiar. It understands that the most effective horror is that which reflects who we are, what we believe, and what we fear becoming. The tiyanak is a mirror held up to society’s unspoken tragedies, and Tiyanak is the vessel that brought that reflection to the big screen in all its terrifying clarity.