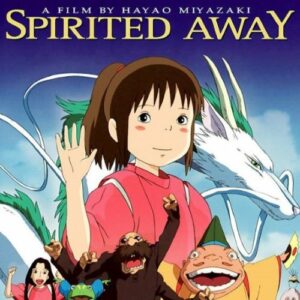

Spirited Away (2001)

| Description | |

|---|---|

| Country of Origin | Japan |

| Language | Japanese |

| Genre | Thriller |

| Cast | Daveigh Chase, Suzanne Pleshette, Miyu Irino |

| Directed by | Hayao Miyazaki |

Hayao Miyazaki’s Spirited Away (2001) is a film deeply rooted in Japanese mythology, blending elements of Shinto beliefs, yōkai folklore, and classic mythological themes into its storytelling. The film’s central setting, the mystical bathhouse run by the witch Yubaba, reflects Shinto purification rituals, where spirits cleanse themselves much like kami (deities) do in sacred waters. Bathing as a form of spiritual renewal is a key aspect of Shinto practices, and the bathhouse in Spirited Away serves as a liminal space between the human and spirit worlds. This connection is reinforced by the presence of the River Spirit, whose pollution and subsequent cleansing parallel real-world concerns about environmental damage and the spiritual significance of nature in Japanese culture.

The spirit world of Spirited Away is populated with creatures resembling yōkai, supernatural beings from Japanese folklore. One of the most intriguing characters, No-Face (Kaonashi), shares traits with the Noppera-bō, a faceless ghost that appears human but reveals an empty visage. No-Face’s transformation into a greedy, devouring entity reflects myths about bakemono, shape-shifters that grow stronger by consuming others. Likewise, Yubaba and her twin sister Zeniba recall Yamauba, the mountain witch, who is both a nurturer and a predator in different folklore accounts. Meanwhile, Haku’s true form as a river dragon aligns with traditional Japanese dragon myths, where these beings are guardians of waterways and symbols of transformation.

Chihiro’s journey in Spirited Away mirrors classic mythological quests, particularly the theme of the hero’s descent into the underworld. Much like Izanagi in Shinto myth, who travels to the land of the dead to rescue his wife, or Orpheus in Greek mythology, who must navigate a supernatural world, Chihiro must prove herself in a foreign realm to save her parents. Her loss of identity when Yubaba takes away her name is a motif found in many myths, where knowing a true name grants power over an individual. The act of reclaiming her name symbolizes self-discovery and growth, a core theme in mythological storytelling.

A recurring mythological test in Spirited Away is the challenge of perception, which Chihiro faces when identifying her transformed parents. This echoes folk tales where heroes must use their wisdom rather than brute force to break an enchantment or solve a puzzle. Her ability to recognize the truth signifies her maturity and inner strength. Similarly, Haku’s role as a forgotten river spirit highlights another key element in mythology—the loss and rediscovery of sacred places. His forgotten name suggests how modern industrialization has severed people’s connection to nature, mirroring real-world environmental concerns.

Ultimately, Spirited Away serves as a modern myth, preserving Japan’s cultural heritage while presenting it in a way that resonates universally. Miyazaki crafts a world where Shinto spirituality, yōkai folklore, and universal mythological themes blend seamlessly into a visually stunning narrative. The film’s deep reverence for nature, its symbolic use of transformation, and its depiction of a hero’s journey make it much more than an animated fantasy—it is a contemporary legend, reminding audiences of the power of mythology in understanding the world and ourselves.