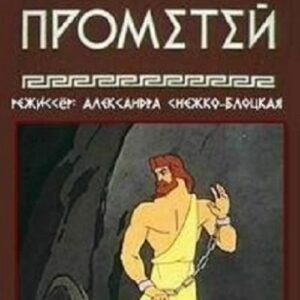

Prometheus (1974)

| Description | |

|---|---|

| Country of Origin | Soviet Union |

| Language | Russian |

| Genre | Animated |

| Cast | Evgeniy Gerasimov, Anna Kamenkova, Aleksey Konsovskiy |

| Directed by | Alexandra Snezhko-Blotskaya |

The 1974 Soviet animated short film Prometheus, directed by Aleksandra Snezhko-Blotskaya, offers a visually arresting and emotionally resonant retelling of the ancient Greek myth through the lens of Soviet-era animation. Produced by the celebrated Soyuzmultfilm studio, the film is part of a larger series that adapts classical Greek mythology into animated form, and it stands out for its poetic fidelity to the source material and its rich thematic undercurrents.

At its core, Prometheus is a tale of defiance, sacrifice, and the human thirst for progress. The story follows the Titan Prometheus, who dares to challenge the supreme god Zeus by stealing fire from Mount Olympus and giving it to humankind. This fire, a symbol of knowledge, creativity, and technological advancement, empowers mortals but comes at a tremendous personal cost to Prometheus. As punishment for his transgression, he is bound to a rock where an eagle endlessly devours his liver—a brutal consequence that emphasizes the theme of eternal suffering for the sake of enlightenment. The film portrays this act not merely as rebellion but as an altruistic gesture born of empathy, setting Prometheus apart as a tragic hero whose love for humanity transcends his fear of divine wrath.

The animation style of the film is both stark and evocative, drawing heavily from the aesthetic of ancient Greek pottery and frescoes, with bold lines and stylized figures that convey grandeur and timelessness. There is a deliberate rhythm to the visuals, one that matches the mythic tone of the story. The gods appear remote and austere, often framed in ways that emphasize their otherworldly power, while humans are shown as fragile and yearning. The landscape is often barren and elemental—an artistic choice that underscores the cosmic scale of Prometheus’s sacrifice and the bleakness of his punishment.

What makes Prometheus particularly compelling is how it communicates profound philosophical and moral ideas within its brief runtime. It invites viewers to reflect on the cost of progress, the role of rebellion in shaping civilization, and the fine line between punishment and martyrdom. The film does not shy away from the darker elements of the myth, including the graphic nature of Prometheus’s torment, but it also uplifts his enduring legacy—his fire becomes the spark of human potential.

As a Soviet-era production, the film carries a subtle ideological subtext as well. The depiction of a lone figure challenging a dominant power for the sake of the collective good can be read as a commentary on the role of individual conscience and sacrifice within a society striving for enlightenment. Yet it remains open to interpretation, allowing audiences from different cultural backgrounds to draw their own meanings from the story.

Though less known in the West, this animated short deserves recognition for its artistic merit and intellectual depth. It is a beautiful and moving interpretation of one of humanity’s oldest stories, rendered with sensitivity and visual flair. For those interested in mythology, animation, or the intersection of art and ideology, Prometheus (1974) is a hidden gem that continues to burn brightly with relevance and emotion.