From Fon to Vodou: The Evolution of Mawu-Lisa in African Spirituality

Mawu-Lisa, the supreme deity in the mythology of the Fon people of Benin, represents a dual-gendered divine force embodying both the moon and the sun, the feminine and the masculine, and the forces of creation and balance. As one of the most revered deities in West African mythology, the variations of Mawu-Lisa across different cultures and traditions showcase the region’s rich spiritual diversity. This article delves into the various interpretations, names, and roles of Mawu-Lisa throughout different belief systems.

Origins and Meaning of Mawu-Lisa

Mawu and Lisa are often depicted as twin deities or a dual-gendered entity that governs the cosmic balance. Mawu is associated with the moon, nighttime, coolness, fertility, and maternal energy, while Lisa is linked to the sun, daytime, heat, strength, and paternal aspects. Together, they represent a holistic vision of the universe, emphasizing equilibrium and harmony in nature.

The Fon people describe Mawu-Lisa as the creator of the world, working in tandem to shape life and order in the cosmos. They entrusted the god Da, the great cosmic serpent, with upholding the universe’s stability, further reinforcing the belief in divine balance.

Variations of Mawu-Lisa in Different Traditions

1. The Ewe Interpretation

Among the neighboring Ewe people of Ghana, Togo, and Benin, Mawu-Lisa takes a similar form but is often referred to simply as Mawu. The Ewe pantheon includes Mawu as a high deity associated with creation and the maintenance of universal order. Unlike in Fon mythology, Lisa’s influence is less emphasized, leading to a more singular representation of the deity’s feminine aspects.

2. Yoruba Equivalents

In Yoruba mythology, there is no direct counterpart to Mawu-Lisa, but similarities exist with deities such as Olodumare and Olorun. Olodumare is the supreme god responsible for creation and destiny, while Olorun governs the heavens and the sun, akin to Lisa’s solar attributes. The Yoruba belief system, like that of the Fon, emphasizes duality, but it does so through different deities rather than a singular dual-gendered god.

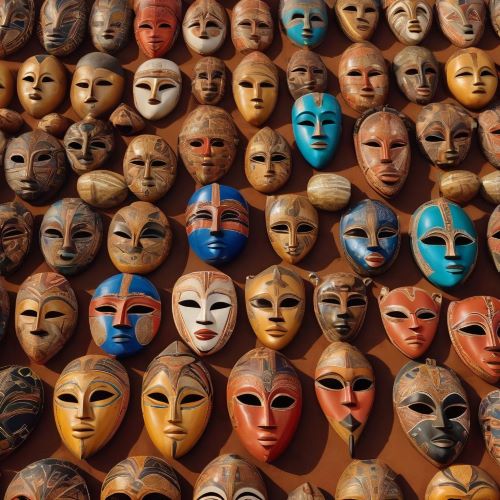

3. Dahomey Vodun Tradition

In the Vodun religious traditions of the Dahomey Kingdom (modern-day Benin), Mawu-Lisa retains a significant role as the ultimate divine entity. However, Mawu is more commonly invoked than Lisa, reflecting an emphasis on the cool, nurturing, and creative aspects of divinity. In Vodun, Mawu is sometimes seen as a distant deity, with intermediary spirits (loa or vodun) acting as conduits for communication and worship.

4. Haitian Vodou Influence

Due to the transatlantic slave trade, West African religious beliefs, including those surrounding Mawu-Lisa, found their way to the Americas, particularly in Haiti. In Haitian Vodou, Mawu’s presence is often syncretized with the Virgin Mary, signifying maternal divinity and compassion. Lisa’s attributes are sometimes absorbed into solar-related spirits, but the duality concept is less emphasized compared to its African roots.

5. Syncretism in Christianity and Islam

With the spread of Christianity and Islam in West Africa, the figure of Mawu-Lisa has undergone further transformations. In Christian interpretations, Mawu is sometimes equated with God the Creator, and Lisa’s characteristics align with Christ as a bringer of light and guidance. In Islamic-influenced regions, Mawu is often associated with Allah, emphasizing the idea of a single, all-encompassing divine entity.

Mawu-Lisa in Modern-Day Worship and Culture

Despite the influence of colonialism and the spread of Abrahamic religions, belief in Mawu-Lisa remains strong among adherents of Vodun and traditional West African religions. In contemporary Benin and Togo, Mawu is often invoked during rituals for fertility, agriculture, and social harmony. The concept of balance embodied by Mawu-Lisa also influences modern discussions on gender, ecology, and spiritual equilibrium.

Artists, writers, and scholars continue to explore Mawu-Lisa’s mythology, highlighting its relevance in understanding African spiritual heritage and its impact on global religious thought. The deity’s dual-natured symbolism has also been embraced by modern feminist and ecological movements, emphasizing the importance of balance in both human and environmental relationships.

Conclusion

The variations of Mawu-Lisa across different cultures highlight the adaptability and endurance of West African spirituality. Whether represented as twin deities, a singular supreme being, or a cosmic force of balance, Mawu-Lisa’s presence remains a testament to the richness of African mythological traditions. As interest in African spirituality continues to grow, understanding these diverse interpretations helps preserve and celebrate the cultural legacy of Mawu-Lisa and the philosophies it represents.