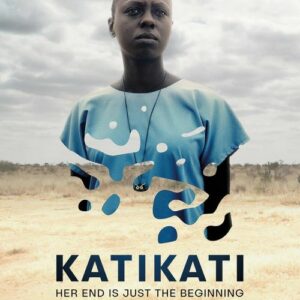

Kati Kati (2016)

| Description | |

|---|---|

| Country of Origin | Kenya |

| Language | Swahili, English |

| Genre | Drama |

| Cast | Nyokabi Gethaiga, Elsaphan Njora |

| Directed by | Mbithi Masya |

Kati Kati (2016), directed by Mbithi Masya, is a visually arresting and thematically rich Kenyan film that blurs the lines between reality and the afterlife, weaving in deeply rooted mythological undertones. Though not overtly presented as a mythological narrative, the film’s core is steeped in symbolic elements and spiritual concepts that echo African cosmological traditions. Set in a mysterious, isolated resort called Kati Kati, the story begins with a woman named Kaleche, who wakes up alone in the wilderness with no memory of who she is. As she is welcomed into a strange community of people who all seem to be in a state of limbo, it becomes apparent that this place is not of the living. The residents are dead, trapped in a purgatory-like existence, haunted by unresolved traumas and regrets. This setting, and the emotional and spiritual journeys of its characters, strongly resemble African beliefs in the afterlife, where the spirits of the dead must find peace before moving on.

The concept of Kati Kati as a transitional space mirrors the spiritual beliefs found in many African mythologies, particularly those that recognize a middle realm between the physical world and the ancestral domain. This is a place where souls pause, reflect, and confront their actions in life. The characters’ inability to leave until they confront their pasts aligns with the idea of spiritual cleansing or reconciliation with one’s ancestors. In this context, Kaleche serves as more than just a protagonist—she becomes a mythic figure, akin to a psychopomp or spiritual guide, one whose arrival catalyzes transformation and reckoning within the community. Her own journey of self-discovery, which eventually reveals a deep and tragic connection to Thoma, the group’s leader, is deeply archetypal. It reflects the mythological theme of forgotten truths and the cyclical nature of existence, where death is not an end but a continuation.

The film’s symbolic use of fire, memory, and nature enriches its mythological texture. Fire, particularly in Thoma’s backstory, represents both destruction and the potential for purification. In many African traditions, fire is a spiritual force—capable of revealing truths and restoring balance. Thoma’s confrontation with his past sins, symbolized through the burning landscape of memory, is a trial by fire in the mythic sense, forcing him to acknowledge the pain he has caused and the guilt he carries. The wilderness surrounding Kati Kati functions as both a physical and metaphysical barrier, a representation of the spirit world where unresolved souls linger. In African cosmologies, the forest or bush is often viewed as the abode of spirits, a transitional space beyond the reach of the everyday.

Dreams and visions play a central role in the narrative, serving as bridges between the visible and invisible, the known and the unknown. These dreamlike sequences resonate with African beliefs in the power of dreams to communicate with the spirit world. Kaleche’s fragmented memories and visions are not just psychological flashbacks—they are revelations, acts of ancestral memory reclaiming space in her consciousness. This aligns with the mythological concept that the dead are not disconnected from the living, but rather continue to communicate through symbols, dreams, and emotional echoes.

What sets Kati Kati apart is how it approaches mythology not as spectacle, but as a quiet, meditative force. It does not introduce deities, monsters, or supernatural events in the traditional sense, yet every frame is imbued with the weight of myth. The characters themselves become archetypes—the guilt-ridden warrior, the wise elder, the lost soul, and the spiritual redeemer—each playing out a personal mythos against the backdrop of a liminal world. Kaleche’s transformation from a confused newcomer to a guiding presence mirrors the hero’s journey common in myths around the world, but here it is grounded in African spiritual logic, where healing and memory are key to transcendence.

Kati Kati can also be seen as a contemporary African myth in the making, a cinematic expression of Afrofuturism that doesn’t rely on high technology or space travel, but instead reclaims African spirituality as a lens for exploring identity and the afterlife. The film’s minimalist aesthetic and emotionally restrained performances allow its mythological themes to resonate more deeply, inviting viewers to engage with the unseen, the unspoken, and the unresolved. It’s a narrative where myth is not ornamental but essential, woven into the characters’ very existence.

In essence, Kati Kati is a mythological tale told in whispers. It reflects the traditional African view that the afterlife is a realm of emotional continuation, not just judgment or reward. By portraying death not as an end, but as a place of reckoning and potential redemption, the film aligns itself with ancient wisdom while crafting a uniquely modern spiritual story. It stands as a compelling example of how African filmmakers are using cinema to re-engage with traditional cosmologies in innovative and emotionally resonant ways. Mythology, in Kati Kati, is not just a theme—it is the invisible architecture holding the story together.