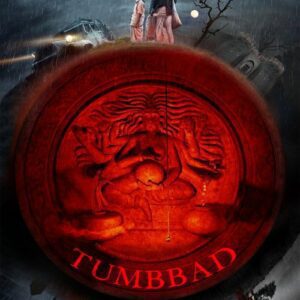

Tumbbad (2018)

| Description | |

|---|---|

| Country of Origin | India |

| Language | Kannada |

| Genre | Thriller |

| Cast | Rishab Shetty, Kishore Kumar, G. Achyuth Kumar, Sapthami Gowda, Manasi Sudhir |

| Directed by | Rishab Shetty |

Tumbbad (2018) is a unique gem in Indian cinema that fuses horror with mythology in a way that feels both haunting and profound. Directed by Rahi Anil Barve and co-directed by Adesh Prasad, the film stands out not only for its chilling atmosphere and visual brilliance but also for the way it crafts a compelling mythological narrative from scratch. At its core, Tumbbad is a tale of greed, but what sets it apart is how this theme is embedded in a rich, fabricated myth that feels deeply rooted in the Indian cultural psyche.

The film introduces the character of Hastar, a fictional forgotten god — the firstborn of the Goddess of Prosperity, who was cursed and erased from all memory after trying to steal both gold and grain. The myth surrounding Hastar feels authentic, as though lifted from ancient scriptures, though it was entirely invented for the film. This creation demonstrates a deep understanding of Indian mythological structure, where gods and demons often embody human qualities and vices, and where cosmic justice plays out over generations. Hastar’s curse — to remain in eternal obscurity, allowed to keep the gold but never touch food — is a powerful metaphor for the destructive nature of unchecked greed. It mirrors the fate of many mythological characters in Hinduism who suffer because they desired more than they were entitled to.

What makes Tumbbad remarkable is how it uses this myth not just as a backdrop but as the narrative engine of the story. The protagonist, Vinayak Rao, becomes obsessed with the treasure hidden in the womb-like shrine beneath the decaying mansion in Tumbbad. His descent into this underground lair over the years becomes a ritualistic journey into his own moral decay. The imagery of entering the earth, tied with the idea of birth, death, and rebirth, echoes Hindu cosmological themes, especially those related to the underworld or Paatal Lok. The underground vault where Hastar resides becomes both a physical and metaphysical space — it’s not just a place of hidden wealth, but of hidden truths about human nature.

The film also touches on the notion of dharma and adharma — righteous and unrighteous conduct — without ever preaching. Vinayak’s actions are driven by greed, and while he uses traditional rituals to contain Hastar and extract gold safely, the very act of engaging with a cursed deity reflects his moral downfall. He passes this obsession on to his son, continuing the cycle of desire and destruction. This intergenerational transmission of greed is another nod to mythological storytelling, where the sins of the father often carry over to the next generation, unless redemption is sought.

What’s striking about Tumbbad is how seamlessly it weaves this mythological horror into a historical setting. Set during British colonial rule, the backdrop of a crumbling empire mirrors the decaying values of the protagonist. The contrast between old-world superstitions and modern ambitions adds a further layer of depth, suggesting that while times change, human flaws like greed remain constant. The colonial setting also allows the film to subtly comment on exploitation — just as the British looted India, Vinayak loots the divine, with equally damning consequences.

Hastar himself, as a creature, is terrifying not only in appearance but in concept. He is a god who is never worshipped, a forgotten being banished to eternal hunger. This idea is powerful because it reflects the Hindu notion that deities lose power without reverence or remembrance. In crafting Hastar, the filmmakers created a mythic being who could easily belong in the ancient pantheon — akin to the rakshasas or asuras whose downfall was always tied to their overreaching desires. His vulnerability to food, his grotesque form, and his eternally repetitive behavior add layers of dread that feel reminiscent of cautionary tales passed down orally in Indian households.

The genius of Tumbbad lies in making the unreal feel completely plausible. There’s no doubt while watching that Hastar could exist, that such a legend might have been whispered in the past but was buried over time. That believability is rooted in the filmmakers’ respect for the logic and language of Indian mythology. The rituals surrounding the descent into Hastar’s shrine, the way flour is used to distract him, and the rules that must not be broken — all these elements echo the structure of real-life mythic rituals and taboos, making the experience immersive and unsettling.

In the end, Tumbbad is more than a horror movie — it is a modern myth, a dark fable that taps into timeless truths about human nature. It speaks of greed not just as a personal flaw but as a cosmic imbalance, one that disturbs the order of the world and brings about ruin. The horror, in this case, is not just external but internal. It is not Hastar who is the true monster, but the insatiable desire that resides in human hearts. In that sense, the film becomes a reflection of the very myths that have shaped Indian cultural consciousness — stories that entertain, warn, and leave you with lingering questions about your own values and choices.

Tumbbad deserves its place as a landmark in Indian cinema, not just for its technical prowess but for the way it reimagines mythology for the modern age. It’s a reminder that the old gods may be gone, but their stories — and the lessons they carry — still haunt us, just like Hastar, lurking in the shadows of our own desires.