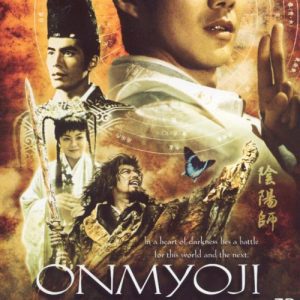

Onmyoji (2001)

| Description | |

|---|---|

| Country of Origin | Japan |

| Language | Japanese |

| Genre | Drama |

| Cast | Mansai Nomura, Hideaki Itō, Hiroyuki Sanada |

| Directed by | Yōjirō Takita |

The 2001 Japanese film Onmyoji is a rare cinematic work that treats mythology not as spectacle alone but as an operating system for reality. Set in the Heian period, the film draws deeply from Japanese cosmology, court ritual, and occult belief to present a world where politics, desire, and disaster are inseparable from the unseen. Rather than positioning magic as an intrusion into normal life, Onmyoji assumes a mythic baseline in which spirits, curses, and cosmic balance are fundamental forces shaping human fate.

Central to the film’s mythological power is the tradition of Onmyōdō, a system rooted in yin-yang philosophy, Taoist cosmology, and Indigenous Japanese spirit belief. In Onmyoji, this system is not simplified for modern audiences but depicted as a living, complex discipline practiced by court diviners who mediate between visible authority and invisible consequence. Spells, talismans, and incantations are portrayed with ritual precision, reinforcing the idea that magic is not about raw power but about alignment with cosmic law. This mythological framing elevates sorcery into a moral and metaphysical responsibility rather than a tool for dominance.

The figure of Abe no Seimei, portrayed with an almost otherworldly calm, functions less as a hero and more as a liminal being. Mythologically, Seimei exists between realms, embodying the archetype of the trickster-sage who understands that balance often requires deception, restraint, and sacrifice. His intelligence is intuitive rather than aggressive, reflecting Japanese mythic traditions in which wisdom lies in perception rather than conquest. The film consistently emphasizes that true power comes from understanding patterns, emotions, and unseen relationships rather than brute force.

Spirits in Onmyoji are not uniformly monstrous or benevolent, and this ambiguity is one of the film’s strongest mythological traits. Shikigami, vengeful ghosts, and summoned entities emerge as reflections of unresolved emotion, obsession, and imbalance. This aligns with Japanese folklore, where yōkai and spirits often arise from human excess rather than external evil. By grounding supernatural threats in emotional and moral disturbance, the film reinforces a mythological worldview in which the spiritual realm mirrors human conduct.

The Heian court itself is depicted as a mythic ecosystem. Silk robes, poetry, music, and rigid etiquette coexist with fear of curses and spirit possession, illustrating a society that openly acknowledges the fragility of order. Mythology here is political. Ritual failures, emotional transgressions, and hidden resentments become catalysts for supernatural collapse. Onmyoji uses this setting to suggest that civilizations fall not when they abandon myth, but when they ignore its warnings.

Visually, the film reinforces mythological thinking through stylized movement, theatrical composition, and symbolic use of space. Darkness and light are not merely aesthetic choices but metaphors for yin and yang in constant negotiation. The measured pacing allows spells and rituals to feel weighty, reinforcing their cosmological significance. Even moments of action feel ceremonial, as though violence itself must obey ritual law.

What makes Onmyoji especially compelling from a mythological perspective is its refusal to moralize simplistically. There are no purely righteous victories, only restored balances that come at personal cost. This echoes East Asian mythic traditions in which harmony, not triumph, is the ultimate goal. The ending does not promise peace, only continuation, reinforcing the idea that balance is temporary and vigilance eternal.

Onmyoji succeeds as a mythological film because it does not retell folktales but dramatizes the worldview that produced them. It treats belief as infrastructure, emotion as catalyst, and ritual as necessity. In doing so, it offers a rare cinematic experience where mythology is not ornamental but structural, reminding the viewer that unseen forces, whether named spirits or human impulses, shape reality far more than appearances suggest.