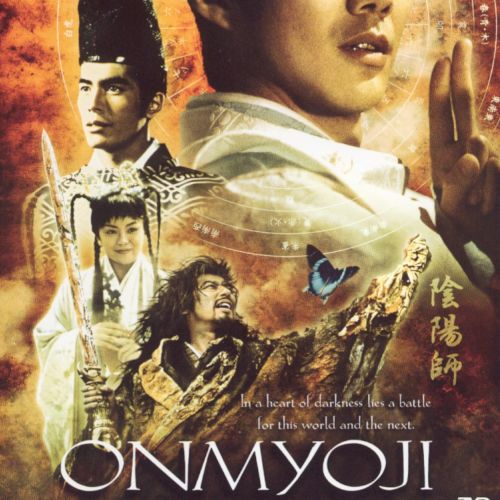

Sacred Treasure Blessing: Amaterasu and Japanese Sacred Tradition

Listen

At a glance

| Description | |

|---|---|

| Mythology | Japanese Mythology |

| Bestowed Upon | Ninigi-no-Mikoto |

| Granted By | Amaterasu |

| Primary Effect | Divine legitimacy, Wisdom, Purity, Valor |

| Conditions Attached | Must uphold harmony, Justice, and Shinto order |

Mythlok Perspective

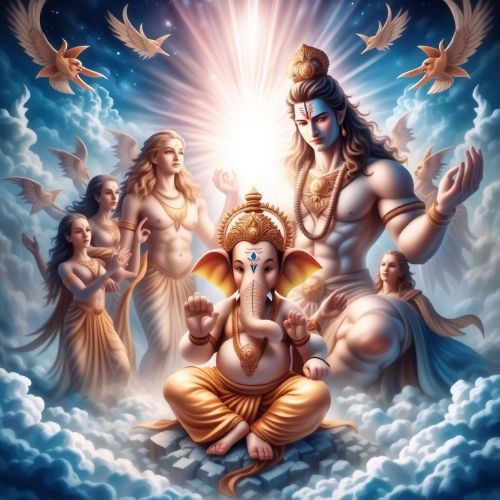

From the Mythlok perspective, Amaterasu’s Sacred Treasure Blessing represents a model of power rooted in restraint rather than expansion. Light here is not overwhelming force but a regulating presence that sustains order. When compared cross-culturally, this triadic system echoes the Egyptian concept of Ma’at or the Indian idea of dharma upheld through balance rather than conquest. Like solar deities elsewhere, Amaterasu governs by alignment, not domination, offering a timeless framework where authority exists to preserve harmony rather than assert supremacy.

Sacred Treasure Blessing

Introduction

In Japanese sacred tradition, Amaterasu Ōmikami stands as the supreme embodiment of light, cosmic order, and moral clarity. As the solar kami and ancestral source of imperial authority, her presence is not abstract but materially expressed through what is known today as the Three Sacred Treasures of Japan. Often described collectively as the Sacred Treasure Blessing, these objects are not gifts in a conventional sense but instruments through which divine legitimacy, ethical responsibility, and cosmic balance are transferred from heaven to earth. Rooted in early Shinto cosmology and preserved in Japan’s oldest chronicles, this blessing continues to shape political ritual, spiritual identity, and cultural memory well into the modern era.

Mythological Background

The mythology of Amaterasu is recorded primarily in the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki, texts compiled in the early eighth century to formalise imperial genealogy and sacred history. Amaterasu is born from the left eye of Izanagi during his purification, immediately associating her with vision, illumination, and truth. Her withdrawal into the Heavenly Rock Cave, Ama-no-Iwato, following the destructive actions of her brother Susanoo, marks a cosmic crisis where light and order vanish from the world. The deities’ efforts to lure her out rely on ritual, laughter, and sacred craftsmanship, most notably the forging of the mirror later known as Yata no Kagami and the stringing of sacred jewels that would become the Yasakani no Magatama. These objects emerge not as symbols after the fact but as active agents in restoring the world itself.

Granting of the Boon/Blessing

The Sacred Treasure Blessing is formally bestowed when Amaterasu prepares the earthly realm for divine governance. Rather than ruling directly, she sends her grandson Ninigi-no-Mikoto to descend from the heavens in the event known as Tenshō Kōrin. Before his descent, she entrusts him with the three treasures, instructing him to revere the mirror as her very spirit. This act establishes a sacred contract between heaven and earth, where rulership is conditional upon alignment with divine order. The blessing is therefore not absolute power but delegated responsibility, anchored in ritual continuity and moral restraint.

Nature of the Boon/Blessing

The Sacred Treasure Blessing operates as a triadic system rather than a singular miracle. Each object expresses a distinct dimension of divine authority while remaining incomplete on its own. The Yata no Kagami represents truth and self-awareness, functioning as a reflective standard against which rulers must measure themselves. The Yasakani no Magatama embodies harmony and spiritual continuity, linking the ruler to the community, the ancestors, and the kami. The Kusanagi no Tsurugi, later associated with heroic figures and warfare, represents disciplined strength rather than aggression. Together, these objects define leadership as balance, where clarity, compassion, and resolve coexist under divine oversight.

Recipients and Key Figures

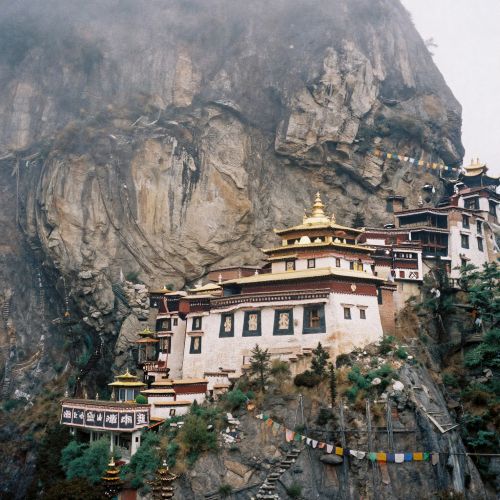

Ninigi’s receipt of the treasures initiates an unbroken lineage culminating in Emperor Jimmu, traditionally regarded as Japan’s first emperor. Through him, the treasures pass to successive rulers, forming the material backbone of imperial legitimacy. Other figures, such as Susanoo, indirectly shape the blessing through the sword’s origin, while Ame-no-Uzume’s ritual dance establishes the performative and ceremonial dimension of sacred authority. Over time, the treasures become associated with specific sites, most notably Ise Grand Shrine, reinforcing the inseparability of place, lineage, and divine presence.

Effects and Consequences

The most enduring consequence of the Sacred Treasure Blessing is the legitimisation of imperial rule as divinely sanctioned rather than militarily imposed. Enthronement ceremonies continue to revolve around the presentation of the regalia, even though they remain hidden from public view. This invisibility reinforces their sanctity, transforming absence into authority. Historically, the treasures have served as stabilising anchors during periods of political transition, signalling continuity even when governance structures shifted. Their preservation through wars, reforms, and constitutional changes demonstrates how deeply embedded the blessing is within Japan’s cultural framework.

Symbolism and Spiritual Meaning

Spiritually, the Three Sacred Treasures articulate a Shinto worldview where power is inseparable from ethical alignment. The mirror demands sincerity and self-reflection, the jewel affirms relational harmony, and the sword insists on disciplined action. Together, they mirror the natural cycle of the sun itself, illuminating without consuming, warming without destroying. Rather than encouraging dominance, the blessing promotes containment, balance, and renewal, reflecting Amaterasu’s role as sustainer rather than conqueror.

Cultural Impact and Legacy

The Sacred Treasure Blessing continues to influence Japanese identity beyond formal religion. The symbolism of Amaterasu informs national imagery, ritual calendars, and artistic expression. Modern interpretations appear in literature, visual media, and even commercial metaphors, where the phrase “three sacred treasures” is repurposed to denote foundational necessities of an era. Yet beneath these adaptations lies an unbroken sacred narrative, one that ties leadership, morality, and cosmic order into a single inherited responsibility. The blessing endures because it remains adaptable without losing its spiritual core.

Source

Philippi, D. L. (1968). Kojiki (Ō no Yasumaro, Trans.). University of Tokyo Press.

Aston, W. G. (1972). Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the earliest times to A.D. 697. Tuttle Publishing.

Herbert, J. (2010). Shinto: At the fountain-head of Japan. Routledge.

Hall, D. A. (2004). Encyclopedia of Shinto. University of Hawai’i Press.

Kirkland, R. (1997). “Akiyama Nanrei: Shinto scholarship in early modern Japan.” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, 24(4), 437-459.

Takenaka, S. (n.d.). Yata no Kagami legends. In Imperial Regalia studies. Tokyo University Press.

The Archaeologist. (2025). The worship of Amaterasu. https://www.thearchaeologist.org/blog/the-worship-of-amaterasu-the-sun-goddess-of-japan

Wikipedia contributors. (2025). Imperial Regalia of Japan. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Imperial_Regalia_of_Japan

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the Sacred Treasure Blessing of Amaterasu?

It is the divine mandate transmitted through the Three Sacred Treasures, establishing legitimacy, moral order, and continuity between heaven and earthly rulers.

What objects form the Sacred Treasure Blessing?

The blessing is embodied in the mirror Yata no Kagami, the jewel Yasakani no Magatama, and the sword Kusanagi no Tsurugi.

Who received the Sacred Treasure Blessing first?

Ninigi-no-Mikoto, grandson of Amaterasu, received the treasures before descending to govern the earthly realm.

Why are the Sacred Treasures hidden from public view?

Their concealment preserves spiritual authority and prevents them from being reduced to symbolic or historical artefacts.

Does the Sacred Treasure Blessing still matter today?

Yes. It remains central to imperial enthronement rituals and continues to symbolise continuity and legitimacy in Japan.