Mwindo : The Epic Hero

Listen

At a glance

| Description | |

|---|---|

| Origin | Nyanga Mythology |

| Classification | Mortals |

| Family Members | Shemwindo (Father), Nyamwindo (Mother) |

| Region | Democratic Republic of Congo, Central African Republic, Republic of Congo |

| Associated With | Miracle birth, Intelligence |

Mwindo

Introduction

At its heart, the Epic of Mwindo is a tale of transformation. Mwindo’s miraculous birth and early displays of power mark him as both human and divine, embodying the intersection of the physical and spiritual realms. Born under a prophecy that foretold his father’s downfall, Mwindo’s journey mirrors the universal hero’s path—from innocence through vengeance to enlightenment.

Performed traditionally by skilled storytellers with music, chant, and rhythmic percussion, the epic served not only as entertainment but as moral education within Nyanga society. Each retelling was a communal act that preserved history, cultural wisdom, and ethical guidance. Mwindo’s trials—facing betrayal, exile, and confrontation with divine beings—reflect the Nyanga belief in balance, justice, and the eventual triumph of moral strength over cruelty and greed.

Through his story, listeners learn that leadership requires more than strength; it demands humility, forgiveness, and respect for both the living and the ancestral spirits. Mwindo’s evolution from an avenging child to a just ruler captures the moral essence of the Nyanga worldview.

Physical Traits

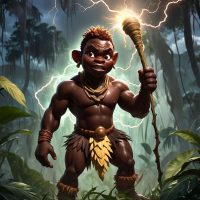

Mwindo’s birth is one of mythology’s most striking miracles. He emerges not from his mother’s womb but from her middle finger, already able to speak, walk, and wield magic. This extraordinary entrance into the world signifies his divine favor and symbolizes wisdom and strength that transcend human limitations. His radiant glow—described as shining like the sun—marks him as a supernatural being blessed by higher powers.

Physically, Mwindo is often compared to a Pygmy, representing both his small stature and immense spiritual might. This duality mirrors the Nyanga philosophy that greatness is not defined by appearance but by moral and intellectual depth. Mwindo’s divine aura and youthful vigor emphasize purity, energy, and the promise of transformation.

His primary weapon, the conga scepter—a flyswatter made from a buffalo’s tail—embodies authority and spiritual power. It serves as both a protector and a tool of judgment, symbolizing his ability to command forces beyond the physical world. Through this scepter, Mwindo channels lightning, restores life, and exercises control over the elements, further reinforcing his status as a hero chosen by destiny.

Family

Mwindo’s family dynamic forms the emotional and moral core of the epic. His father, Shemwindo, the chief of Tubondo, is a ruler corrupted by fear and pride. When a prophecy reveals that his son will dethrone him, Shemwindo decrees that no male child may live. Six of his seven wives bear daughters, but the seventh, Nyamwindo, gives birth to the prophesied boy.

From the moment of his birth, Mwindo becomes the target of his father’s wrath. Shemwindo’s repeated attempts to kill his son—by spear, burial, and even drowning him inside a drum—are all thwarted by Mwindo’s divine resilience. His survival symbolizes hope against oppression and the inevitability of truth overcoming tyranny.

As Mwindo grows, his aunt Iyangura and her husband, Mukiti, a river god, provide sanctuary and guidance, representing the role of extended family and the divine in nurturing moral growth. Mwindo’s journey is marked by a gradual shift—from vengeance against his father to forgiveness and reconciliation. Ultimately, when Shemwindo repents and accepts his son’s rule, the narrative transforms into a story of redemption and restored harmony, teaching that justice must coexist with mercy.

Other names

Mwindo’s name carries layers of meaning deeply rooted in the Nyanga language and cosmology. Often translated as “the little one who walks” or “the child born already walking and talking,” it reflects both his miraculous birth and his immediate readiness to act. He is also known by titles such as Kabutwa-Kenda, which translates to “the little one just born yet walking,” emphasizing his precocity and divine nature.

In various regional renditions, Mwindo may appear under alternate spellings—Mwendo, Mwinndo, or Mwendu—but the essence of his identity remains consistent: a miraculous child who challenges injustice and embodies the moral ideals of courage, balance, and renewal. These names are invoked in ritual songs and performances that celebrate his heroism, reinforcing his symbolic role as a bridge between humanity and the divine.

Powers and Abilities

Mwindo’s powers place him among the greatest mythic heroes of Africa. From birth, he exhibits extraordinary abilities that mark him as a being beyond mortal limits. He is invincible to weapons, burial, and drowning, symbolizing the purity and resilience of divine justice. His magical conga scepter serves as both weapon and conduit for supernatural energy, allowing him to summon lightning, defeat gods, and even resurrect the dead.

His connection to nature and the spiritual realm is profound. Mwindo commands storms and lightning, grows banana forests in a single day, and communes with spirits and deities alike. During his journey, he travels through multiple worlds—the earth, the underworld ruled by Muisa, and the heavens of Sheburungu—demonstrating his role as a mediator between life and death, chaos and order.

Yet his greatest power is not destruction but transformation. After defeating his enemies, including the thunder god Nkuba and the serpent demon Kirimu, Mwindo learns to use his gifts for creation and healing rather than vengeance. His journey culminates in moral enlightenment, where he vows to rule justly, protect his people, and uphold the sacred balance of life. In this, Mwindo becomes not merely a conqueror but a symbol of wisdom and renewal.

Modern Day Influence

The legacy of Mwindo extends far beyond the oral traditions of the Congo. Since its transcription in the mid-20th century, the Mwindo Epic has gained international recognition as a masterpiece of African mythology and comparative literature. Scholars frequently liken Mwindo’s journey to those of Gilgamesh, Hercules, and Rama, highlighting the universal nature of the hero’s quest across civilizations.

Modern adaptations have reintroduced Mwindo to new audiences. Aaron Shepard’s “The Magic Flyswatter: A Superhero Tale of Africa” (2008) retells the myth for younger readers, portraying Mwindo as an African superhero whose powers stem from intelligence and moral strength. Theater productions, such as the Seattle Children’s Theatre’s “Mwindo”, bring his adventures to life through music and dance, preserving the story’s performative roots.

In academic and cultural settings, Mwindo is studied as a symbol of ethical leadership, resilience, and postcolonial identity. His narrative resonates in contemporary Africa as an allegory for just governance and community reconciliation. Across the diaspora, Mwindo’s story has inspired reinterpretations in literature, visual art, and digital storytelling, often reimagining him as a mythic archetype of balance between tradition and progress.

Mwindo remains a timeless emblem of transformation—the child born speaking truth to power, who learns that real strength lies in forgiveness. His tale continues to echo the enduring wisdom of the Nyanga people, reminding the world that even in myth, the greatest victory is over one’s own heart.

Related Images

Source

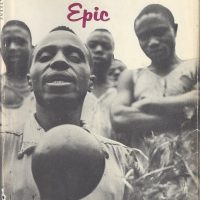

Biebuyck, D. P., & Mateene, K. (1969). The Mwindo Epic: From the Banyanga People of the Congo. University of California Press.

Encyclopedia.com. (2025, August 13). Mwindo. Retrieved from https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/mwindo

Fabula Hub. (n.d.). The Epic of Mwindo. Retrieved from https://fabulahub.com/en/story/the-epic-of-mwindo

Wikipedia. (n.d.). Mwindo Epic. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mwindo_epic

CrashCourse World Mythology. (2024, September 30). The Mwindo Epic (Episode 29). Retrieved from https://thecrashcourse.com/courses/the-mwindo-epic-crash-course-world-mythology-29/

Cram.com. (n.d.). Cultural Values in the Mwindo Epic. Retrieved from https://www.cram.com/essay/Cultural-Values-In-The-Mwindo-Epic

Biebuyck, D. P., & Mateene, K. (1969). The Mwindo Epic from the Banyanga. University of California Press.

Vansina, J. (1990). Paths in the Rainforests: Toward a History of Political Tradition in Equatorial Africa. University of Wisconsin Press.

Okpewho, I. (1992). African Oral Literature: Backgrounds, Character, and Continuity. Indiana University Press.

Scheub, H. (2000). A Dictionary of African Mythology: The Mythmaker as Storyteller. Oxford University Press.

Finnegan, R. (2012). Oral Literature in Africa. Open Book Publishers.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is lorem Ipsum?

I am text block. Click edit button to change this text. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

What is lorem Ipsum?

I am text block. Click edit button to change this text. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

What is lorem Ipsum?

I am text block. Click edit button to change this text. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

What is lorem Ipsum?

I am text block. Click edit button to change this text. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

What is lorem Ipsum?

I am text block. Click edit button to change this text. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.