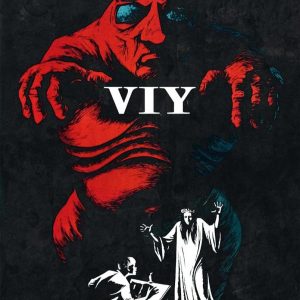

Viy (1967)

| Description | |

|---|---|

| Country of Origin | Soviet Union |

| Language | Russian |

| Genre | Horror |

| Cast | Leonid Kuravlyov, Natalya Varley, Alexei Glazyrin, Vadim Zakharchenko, Nikolai Kutuzov |

| Directed by | Konstantin Yershov, Georgi Kropachyov |

The 1967 Russian horror-fantasy film Viy, directed by Konstantin Yershov and Georgi Kropachyov, remains one of the most authentic cinematic adaptations of Slavic mythology. Based on Nikolai Gogol’s short story of the same name, Viy blends eerie folklore, religious imagery, and moral allegory into a haunting visual experience that captures the very soul of Eastern European myth. This film is not only a cornerstone of Soviet-era horror but also one of the few works to faithfully bring ancient Slavic mythological entities to life on screen.

At its heart, Viy is a story about faith, fear, and the supernatural. The protagonist, Khoma Brutus, a philosophy student from a Kyiv seminary, is sent to perform prayer rites for three nights over the corpse of a young woman in a remote village. What begins as a ritual duty quickly descends into a nightmarish confrontation with the dark forces of the underworld. The deceased maiden, revealed to be a witch, rises from her coffin each night to torment him, culminating in the terrifying appearance of Viy himself – a demonic creature with heavy iron eyelids whose gaze brings death.

From a mythological standpoint, Viy serves as a cinematic preservation of Slavic pagan beliefs that survived beneath the surface of Christianized folklore. The film’s titular creature, Viy, is not a simple invention of horror fiction but a reflection of deep-rooted mythic symbolism. In Ukrainian and Russian folklore, Viy is described as a chthonic being—connected to the earth and the underworld—whose eyes possess the power to kill anyone they see. His name derives from the old Slavic word “vyey,” meaning “to cover” or “veil,” symbolizing hidden truths, death, and forbidden knowledge. This mythic resonance makes Viy more than a ghost story; it’s an exploration of the tension between human rationality and primal fear.

What makes Viy so distinctive is its treatment of magic and the supernatural as a natural part of the peasant worldview. The film presents witchcraft, demonic forces, and protective rituals as everyday realities, deeply ingrained in rural life. From protective chalk circles to sacred prayers and church bells, every scene reflects an authentic depiction of how ancient communities viewed the battle between light and darkness. The peasant world of Viy exists in a liminal space where Christianity overlays paganism, resulting in a spiritual duality that defines Slavic mythological tradition.

Visually, Viy is remarkable for its use of practical effects that evoke an atmosphere of dread without relying on modern technology. The floating witch, the grotesque demons, and the climactic summoning of Viy are created through hand-crafted illusions, giving the film a theatrical, dreamlike quality. The final sequence, when Viy himself is revealed, is one of the most memorable in Russian cinema. His enormous, stone-heavy eyelids—lifted only by grotesque attendants—are an unforgettable embodiment of ancient terror. This creature design perfectly captures how Slavic mythology imagines evil: not sleek or seductive, but ancient, heavy, and bound by the earth.

Beneath the horror lies a moral tale drawn directly from mythological tradition. Khoma’s arrogance, skepticism, and sinfulness bring about his downfall. His failure to maintain faith during his vigil and his moral weakness in the face of temptation mark him as a man spiritually unprepared to face the supernatural. This theme echoes the mythic archetype of the hero who must confront not only monsters but his own inner corruption. In Slavic folklore, such stories often serve as cautionary tales about the dangers of pride and the importance of spiritual strength.

What sets Viy apart from typical Western horror is its refusal to fully rationalize or explain its mythological world. There are no scientific answers, no clear good or evil, only the acceptance that supernatural forces coexist with human life. This approach gives Viy a timeless mythic dimension, aligning it more closely with ancient oral storytelling than with modern horror cinema. Every detail, from the rustic Ukrainian landscapes to the haunting church interiors, reinforces the authenticity of its mythological roots.

The film also carries subtle social undertones. Released in the Soviet Union during a time when open discussion of religion and folklore was restricted, Viy managed to sneak spiritual and mythological themes into mainstream cinema. Its popularity can be attributed to the deep cultural connection Russians and Ukrainians felt with their ancestral myths. By adapting Viy, Gogol’s tale became not only a story about horror but a preservation of cultural memory — an artistic reclamation of Slavic mythic identity under a regime that often sought to suppress it.

In retrospect, Viy stands as a cinematic bridge between myth and modernity. It is both a ghost story and a mythological allegory, presenting a worldview where the unseen is more powerful than the seen. The film’s lasting appeal lies in its ability to make mythology feel alive — to make us believe, if only for a moment, that the world is still haunted by the spirits of old. Its influence can be traced in later works of folk horror, from The Witch (2015) to The VVitcher series, all of which draw from the same deep well of myth and folklore.

For viewers today, Viy is not just an old Soviet curiosity but a vital piece of cinematic mythology. Its blend of rural mysticism, moral allegory, and genuine horror captures the very essence of Eastern European folklore. It reminds us that mythology isn’t just a collection of old stories—it’s a living force that shapes how people confront fear, death, and the unknown.