Admetus: The Hospitable King

Listen

At a glance

| Description | |

|---|---|

| Origin | Greek Mythology |

| Classification | Mortals |

| Family Members | Pheres (Father), Alcestis (Wife), Eumelus (Son) |

| Region | Greece |

| Associated With | Royalty, Hospitality |

Admetus

Introduction

Admetus, the king of Pherae in Thessaly, holds a distinctive place in Greek mythology. Unlike the great warriors or trickster kings who dominate Hellenic tales, Admetus is remembered for his humanity, compassion, and the extraordinary bond he shared with both gods and mortals. His story is most famously preserved in Euripides’ play Alcestis, where themes of love, sacrifice, and mortality converge in a deeply human narrative. Known for his extraordinary hospitality, Admetus attracted the favor of Apollo himself, who served him in disguise, a rare reversal in the divine–mortal hierarchy. Yet his life also carried the shadow of fate, culminating in the tragic bargain that required his beloved wife, Alcestis, to die in his place. Through this myth, Admetus embodies the tension between privilege and responsibility, mortal weakness and divine grace.

Physical Traits

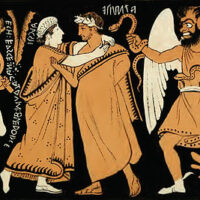

Descriptions of Admetus in ancient texts are sparse, as his myth focuses more on character than appearance. However, artistic depictions present him as a youthful, noble figure, often adorned in the flowing robes of Thessaly. Vase paintings and Roman frescoes place him alongside Alcestis or Apollo, highlighting his regal bearing. In drama, his presence is conveyed less through physical might and more through emotional intensity—Euripides portrays him as a man capable of both generosity and fragility, torn between his fear of death and his gratitude for Alcestis’ sacrifice. This duality suggests that his defining traits were not external but internal: a dignified host, a flawed husband, and a mortal wrestling with the inevitability of loss.

Family

Admetus was born into a royal lineage as the son of King Pheres, the founder of Pherae, and either Periclymene or Clymene, depending on the source. His late birth to elderly parents was seen as a sign of destiny, placing him in a unique position as heir to the throne. The most significant figure in his life, however, was Alcestis, daughter of Pelias of Iolcus. Their marriage became legendary because it required divine assistance: Apollo, grateful for Admetus’ kindness, helped him win Alcestis’ hand by yoking a lion and a boar to a chariot—an impossible feat without the god’s aid. Together, Admetus and Alcestis had children, including Eumelus, who would later distinguish himself as a warrior in the Trojan War. The family’s story, however, was overshadowed by tragedy, as Alcestis’ willingness to die for her husband became the defining moment of their legacy.

Other names

The name Admetus (Ἄδμητος) is derived from Ancient Greek and is often translated as “untamed” or “untameable,” hinting at the stubborn threads of fate entwined in his life. While the name itself remains constant across sources, later literature and poetry occasionally furnished him with symbolic epithets. In Roman interpretations, he was sometimes styled “Apollo’s Beloved,” a reflection of the rare intimacy between a god and a mortal king. In Thessalian tradition, he was remembered primarily by his royal title, the King of Pherae, which preserved his status as both a ruler and a cultural figure within the mythological landscape. Unlike heroes such as Heracles or Achilles, whose names were bound to feats of strength, Admetus’ identity was tied to his character and his relationship with the divine.

Powers and Abilities

Unlike mythological heroes blessed with superhuman abilities, Admetus’ “powers” were shaped by his moral qualities and the divine favor they attracted. His generosity and hospitality were legendary, setting him apart in a culture that valued xenia, or the sacred duty of hosting strangers. It was this virtue that won Apollo’s devotion, leading the god to serve Admetus for a year as a herdsman, during which the flocks multiplied miraculously. Admetus’ most unusual gift came when Apollo persuaded the Fates to allow him to evade death, provided another life was offered in his stead. This loophole, while extraordinary, exposed the moral weight of his privilege: someone else had to pay the price for his survival. Ultimately, Alcestis became that substitute, laying bare the tension between divine generosity and mortal obligation. Later, Heracles’ intervention restored balance, retrieving Alcestis from the clutches of Thanatos and underscoring how Admetus’ greatest strength—his capacity to inspire loyalty and aid—was rooted not in force, but in relationships.

Modern Day Influence

The myth of Admetus continues to resonate across literature, philosophy, and the arts. Euripides’ Alcestis remains a cornerstone of classical theater, frequently staged to explore the complexity of sacrifice and the human struggle with mortality. In the Renaissance and Romantic periods, the story inspired operas, poems, and paintings, including works by Handel and Frederic Leighton. Philosophers and literary critics have often reflected on Admetus’ moral dilemma, using it as a lens to discuss the ethics of substitutionary sacrifice and the human desire to escape fate. In modern psychology, Alcestis’ act is sometimes interpreted as a metaphor for emotional labor and self-sacrifice in relationships, with Admetus symbolizing the burden of guilt that follows. Contemporary theater and film occasionally revisit the myth, recasting it in modern settings where questions of love, mortality, and responsibility remain deeply relevant. In these reinterpretations, Admetus’ legacy is not just as a king of Thessaly, but as a mirror for timeless human struggles.

Related Images

Source

Britannica. (n.d.). Admetus Greek Mythology, King of Pherae & Fate. Retrieved September 2, 2025, from https://www.britannica.com/topic/Admetus

Greek Mythology.com. (n.d.). Admetus. Retrieved September 2, 2025, from https://www.greekmythology.com/Myths/Mortals/Admetus/admetus.html

Wikipedia contributors. (2025). Admetus of Pherae. Wikipedia. Retrieved September 2, 2025, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Admetus_of_Pherae

M Dyson. (1988). Alcestis’ children and the character of Admetus. In The Journal of Hellenic Studies. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-hellenic-studies/article/alcestis-children-and-the-character-of-admetus/7FED1E9ECB879D6F6DD412B9D3F7D6C8

King Admetus in Greek Mythology. (n.d.). https://www.greeklegendsandmyths.com/admetus.html

Avi Kapach. (2023). Admetus – Mythopedia. https://mythopedia.com/topics/admetus/

Contributors to Gods of Olympus Wiki. (n.d.). Admetus (son of Pheres) | Gods of Olympus Wiki | Fandom. https://gods-of-olympus.fandom.com/wiki/Admetus_(son_of_Pheres)