Listen

At a glance

| Description | |

|---|---|

| Origin | Cambodian Mythology |

| Classification | Hybrids |

| Family Members | Krong Reap (Father), Hanuman (Husband), Macchanu (Son), |

| Region | Cambodia |

| Associated With | Mermaid |

Sovanna Maccha

Introduction

Sovanna Maccha, also known as Suvannamaccha, occupies a unique and beloved place in Cambodian mythology as one of the most memorable figures in the Reamker, the Khmer adaptation of the Indian Ramayana. Her name translates to “Golden Mermaid,” a title that reflects both her radiant appearance and her symbolic role within Southeast Asian storytelling. Unlike the Indian epic, where aquatic beings play little narrative importance, the Reamker introduces Sovanna Maccha as a pivotal character whose actions directly influence the outcome of Rama’s divine mission.

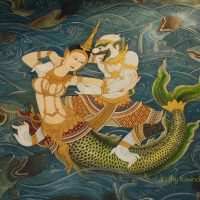

Her story unfolds during the construction of the causeway to Lanka, where Rama’s army struggles against mysterious forces undoing their labor each night. As the commander of these underwater disruptions, Sovanna Maccha initially appears as an antagonist bound by loyalty to her father, the demon king Ravana, known in Khmer tradition as Krong Reap or Thotsakan. Yet her encounter with Hanuman transforms the conflict into one of romance, reconciliation, and moral choice. Through Sovanna Maccha, Cambodian mythology explores themes of love that transcends lineage, duty challenged by compassion, and harmony forged between opposing worlds.

Physical Traits

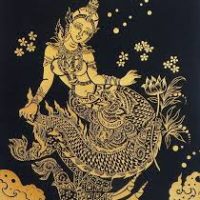

Sovanna Maccha is traditionally depicted as a breathtaking mermaid princess with a human upper body and a fish tail crafted from shimmering gold. This golden hue is not merely decorative; in Khmer symbolism, gold represents prosperity, divine favor, and cosmic balance. Her human form is portrayed with serene facial features, almond-shaped eyes, and long flowing hair that moves like water itself, reinforcing her connection to the oceanic realm.

In classical Cambodian art and dance, her elegance is emphasized through fluid movements designed to mirror ocean currents. She is often adorned with ornate jewelry, armlets, necklaces, and a royal crown that signifies her noble birth. Temple murals and royal ballets frequently contrast her graceful aquatic presence with Hanuman’s vigorous, terrestrial energy, visually reinforcing the union of water and land. These depictions have remained remarkably consistent across centuries, preserving her identity as both regal and otherworldly.

Family

Within the Reamker, Sovanna Maccha is identified as the daughter of Ravana, the fearsome ruler of Lanka. This lineage places her firmly within the adversarial camp opposing Rama, creating an inherent tension between inherited duty and personal agency. Unlike many demon-born figures who remain steadfastly aligned with Ravana, Sovanna Maccha’s narrative arc is defined by her capacity to choose differently.

Her union with Hanuman results in the birth of Macchanu, a hybrid figure possessing the torso of a monkey and the tail of a fish. Macchanu later appears as a guardian of Lanka, initially unaware of his parentage, and unknowingly confronts his own father in battle. This generational continuation reinforces Sovanna Maccha’s role as a bridge between worlds—demonic and divine, aquatic and terrestrial—making her lineage one of reconciliation rather than perpetual conflict.

Other names

Across Southeast Asia, Sovanna Maccha is known by several regional names that reflect linguistic and cultural adaptations of her legend. In Khmer, she is written as សុវណ្ណមច្ឆា and pronounced Sovanna Maccha or Sovann Maccha. Thai traditions refer to her as Suvannamaccha or Suphan Matcha, while older Sanskrit-derived forms such as Suvarṇamatsya emphasize her identity as the “Golden Fish.”

These variations do not represent different characters but rather localized expressions of the same mythological figure. Each name preserves her defining traits while integrating seamlessly into local performance traditions, literature, and oral storytelling. The consistency of her narrative across regions highlights the shared cultural currents that shaped Southeast Asian reinterpretations of the Ramayana.

Powers and Abilities

As a mermaid princess, Sovanna Maccha commands the seas with authority and precision. She leads an organized army of mermaids capable of dismantling massive stone structures beneath the waves, demonstrating both supernatural strength and tactical intelligence. Her ability to breathe underwater, summon aquatic forces, and navigate ocean depths effortlessly positions her as a sovereign figure of the marine realm.

Beyond physical power, her most compelling ability lies in her emotional intelligence and independence of thought. When confronted by Hanuman, she does not remain bound by blind obedience to Ravana’s command. Instead, she evaluates the larger moral stakes of the conflict and ultimately aids Rama’s cause by ordering the submerged stones returned to the surface. This decision transforms her from saboteur to silent architect of victory, illustrating that wisdom and compassion can rival brute strength in mythological storytelling.

Modern Day Influence

Sovanna Maccha continues to hold a vibrant presence in contemporary Cambodian culture. She is a central figure in Robam Sovanna Maccha, a classical dance performance taught in royal ballet schools and staged during festivals, state ceremonies, and cultural exhibitions. Her image also appears prominently in temple murals, museum collections, and modern visual art inspired by Khmer heritage.

In both Cambodia and Thailand, Sovanna Maccha has become a symbol of prosperity, love, and reconciliation. Her likeness is often used in decorative art and commercial spaces as a charm associated with abundance and harmony. Modern interpretations increasingly frame her as a figure of feminine agency—one who chooses empathy over inherited enmity. Through literature, performance, and digital media, Sovanna Maccha remains a powerful reminder of Southeast Asia’s unique mythological voice within the broader Ramayana tradition.

Related Images

Source

Chandler, D. P. (1998). The history of Cambodia. Westview Press.

Holt, J. C. (2009). Brains and brawn in the Ramayana: Hanuman’s story in Cambodian dance theatre. In P. Lopéz (Ed.), Buddhism and the performing arts of Cambodia (pp. 45-67). McFarland.

Jobes, G. (1962). Dictionary of mythology, folklore and symbols. Scarecrow Press.

Pantheon.org. (n.d.). Suvarnamacha. https://pantheon.org/articles/s/suvarnamacha.html

Wikipedia. (2024). Robam Sovann Maccha. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robam_Sovann_Maccha

Wikipedia. (2024). Suvannamaccha. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Suvannamaccha

Brandon, J. R. (1967). Theatre in Southeast Asia. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Groslier, B. P. (1966). Angkor and Cambodia in the Sixteenth Century. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Bizot, F. (2004). The Gate. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf.

Thompson, A. (2004). Dance and the Ramayana in Cambodia. Asian Theatre Journal, 21(2), 145–163.

Jacobsen, T. (2008). Lost Goddesses: The Denial of Female Power in Cambodian History. Copenhagen: NIAS Press.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who is Sovanna Maccha in Cambodian mythology?

Sovanna Maccha is a golden mermaid princess from the Reamker, Cambodia’s version of the Ramayana, known for her romance with Hanuman.

Is Sovanna Maccha part of the original Ramayana?

No, she does not appear in Valmiki’s Indian Ramayana and is unique to Southeast Asian adaptations.

What is the meaning of the name Sovanna Maccha?

Her name means “Golden Mermaid” or “Golden Fish,” symbolizing prosperity and divine beauty.

Who are Sovanna Maccha’s parents?

She is the daughter of Ravana, the demon king of Lanka, known as Krong Reap in Khmer tradition.

Why is Sovanna Maccha important in the Reamker?

Her decision to help Hanuman allows the causeway to Lanka to be completed, altering the course of the epic.