Tagaro : The Melanesian Creator Figure of Vanuatu

Listen

At a glance

| Description | |

|---|---|

| Origin | Vanuatu Mythology |

| Classification | Gods |

| Family Members | Suqe-matua (Brother) |

| Region | Vanuatu |

| Associated With | Creation, Trickster |

The Mythlok Perspective

From the Mythlok perspective, Tagaro represents creation as an ongoing negotiation rather than a completed act. His intelligence lies in correction, foresight, and balance, not domination. When compared cross-culturally, Tagaro mirrors figures like Maui in Polynesian traditions and Loki in Norse narratives, yet differs in moral emphasis. Where Loki disrupts and Maui challenges limits, Tagaro stabilizes through wisdom. This contrast highlights a Melanesian worldview where survival depends on adaptability and restraint rather than conquest.

Tagaro

Introduction

Tagaro occupies a central place in the mythic imagination of Vanuatu, particularly across the northern islands of the archipelago. His stories form a foundational layer of Melanesian cosmology, explaining how the world took shape, why order and disorder coexist, and how human life must constantly negotiate between wisdom and error. In many traditions, Tagaro is presented as a creator figure whose decisions establish land, life, and social norms, yet he is also a cunning and adaptive presence whose intelligence allows him to correct mistakes and outwit destructive forces. This layered personality makes Tagaro less of a distant cosmic god and more of an active participant in the unfolding world. Across generations, his narratives have functioned not only as sacred history but as living frameworks through which communities understand morality, balance, and survival.

Physical Traits

Descriptions of Tagaro’s appearance remain deliberately fluid, reflecting the oral nature of Vanuatu’s storytelling traditions. Rather than fixating on a defined divine form, storytellers emphasize what Tagaro does and how he moves through the world. In some accounts, he appears human-like, capable of walking the land, climbing trees, shaping objects, and speaking directly with people. In others, he is associated with elevated spaces such as the sky or towering trees, suggesting his role as a mediator between earthly and cosmic realms. This absence of a rigid physical image allows Tagaro to adapt to different narrative needs, reinforcing the idea that power in Melanesian belief is expressed through action and consequence rather than visual grandeur.

Family

Tagaro’s relationships with his family form the dramatic backbone of many creation stories. He is most often portrayed alongside brothers whose actions contrast sharply with his own. Among these figures, Suqe-matua appears frequently as a rival or counterpart whose attempts at creation go awry. Where Tagaro’s efforts bring stability and coherence, Suqe’s interventions introduce error, danger, or imbalance. This recurring pattern creates a mythic explanation for why the world contains both harmony and hardship. In some regional traditions, Tagaro is also connected to ancestral lineages, with certain families tracing their origins back to encounters with him. These genealogical links blur the boundary between divine history and human ancestry, grounding cosmic events in lived social identity.

Other names

Across the linguistic mosaic of Vanuatu, Tagaro’s name appears in multiple forms, each shaped by local language and cultural emphasis. Variants such as Tagaroa, Takaro, and Tangaro reflect both phonetic shifts and deeper regional interpretations of his role. In the northern islands, cognate names derived from Tagaro are even used today to refer to the Christian God, illustrating how indigenous cosmology adapted rather than disappeared during Christianization. This continuity demonstrates how Tagaro’s identity expanded over time, allowing an ancient creator figure to remain relevant within new religious frameworks while retaining echoes of his original mythic authority.

Powers and Abilities

Tagaro’s defining ability is creation, but it is a form of creation rooted in experimentation and correction rather than effortless perfection. He shapes landforms, brings living beings into existence, and establishes customs that structure communal life. His creative acts often involve trial and error, especially when contrasted with the failed or flawed attempts of his brothers. Beyond creation, Tagaro possesses transformative intelligence. He can fashion living beings from fruit or crafted images, move freely between sky and earth, and anticipate disasters before they unfold. In several stories, his foresight allows him to survive cataclysmic floods or destructive events by preparing refuges in advance. These abilities frame him not merely as a god of power but as a teacher whose stories emphasize adaptability, planning, and respect for balance.

Modern Day Influence

Despite the dominance of Christianity in contemporary Vanuatu, Tagaro has never vanished from cultural memory. His presence continues through oral storytelling, place-based legends, and cultural heritage narratives tied to specific islands such as Ambae, Pentecost, and Maewo. Landscapes marked by rocks, caves, and ancient trees are often associated with his deeds, transforming geography into a living archive of myth. In academic discourse, Tagaro is frequently cited as a key example of Melanesian cosmology, while in cultural revival movements he symbolizes indigenous knowledge systems and ecological awareness. Comparisons with global trickster and creator figures have further brought Tagaro into modern discussions, positioning him as both uniquely Ni-Vanuatu and universally resonant.

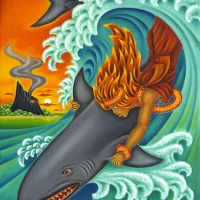

Related Images

Source

Confinity. (2025, December 21). Vanuatu heritage: Museums, landmarks & culture. Retrieved January 20, 2026, from https://www.confinity.com/countries/vanuatu

Codrington, R. H. (1891). The Melanesians: Studies in their anthropology and folklore. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Douglas, B. (2010). The troubled histories of a stranger god: Religious change, cosmology, and history in Melanesia. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 52(2), 351–383.

Gardissat, P., & Mezzalira, N. (Eds.). (2005). Nabanga: An illustrated anthology of the oral traditions of Vanuatu. Port Vila, Vanuatu: Vanuatu National Cultural Council.

Godchecker. (2023, June 15). Tagaro – Vanuatuan creator god. In Godchecker: Your guide to the gods. Retrieved January 20, 2026, from https://www.godchecker.com/melanesian-mythology/tagaro/

Keller, H. (1916). Tagaro and his family. In W. A. Fraser (Ed.), Oceanic mythology (pp. 83–95). London, UK: G. G. Harrap.

Melanesian mythology. (n.d.). (2006 version). In Wikipedia. Retrieved January 20, 2026, from

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Melanesian_mythology

Codrington, R. H. (1891). The Melanesians: Studies in Their Anthropology and Folk-Lore. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Layard, J. (1942). Stone Men of Malekula: Vanuatu in the Melanesian World. London: Chatto & Windus.

Bonnemaison, J. (1994). Arts of Vanuatu. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who is Tagaro in Vanuatu traditions?

Tagaro is a central creator figure in Melanesian belief systems, especially in northern Vanuatu, associated with creation, wisdom, and balance.

Is Tagaro a god or a trickster?

Tagaro embodies both roles. He is a creator god whose intelligence and adaptability often take the form of trickery used to restore order.

What is Tagaro’s relationship with Suqe-matua?

Suqe-matua is often portrayed as Tagaro’s rival brother whose flawed actions contrast with Tagaro’s successful creations.

Is Tagaro connected to Tangaroa of Polynesian traditions?

Linguistically and conceptually, Tagaro is related to Tangaroa, though their roles differ across Melanesian and Polynesian cultures.

Does Tagaro still influence modern Vanuatu culture?

Yes. His stories persist through oral tradition, cultural heritage narratives, and symbolic connections to land and identity.