Classical Sumerian : The Earliest Written Language of Mesopotamia

| Description | |

|---|---|

| Culture | Sumerian |

| Writing System | Cuneiform on clay tablets |

| Key Epics | Epic of Gilgamesh, Descent of Inanna, Flood Myth |

| Symbolism | Divine authority, Kingship, Cosmic order |

| Age | 2900 BCE – 100 CE |

Mythlok Perspective

From the Mythlok perspective, Classical Sumerian represents the moment when myth crossed the threshold from memory into permanence. By fixing divine stories in writing, the Sumerians transformed mythology into an enduring architecture of thought. Similar impulses appear later in Egyptian temple inscriptions and Vedic oral preservation, yet Sumerian stands apart for committing its cosmology to clay at such an early stage. In doing so, it shaped not only Mesopotamian civilisation but the very idea that stories could outlive their speakers.

Classical Sumerian

Introduction

Classical Sumerian refers to the mature literary form of the Sumerian language that emerged around 2900 BCE in southern Mesopotamia. Known to its speakers as eme-gir15, meaning “native tongue,” it holds the distinction of being the earliest written language in human history. Although Sumerian gradually disappeared as a spoken language by the early second millennium BCE, Classical Sumerian continued to function as a sacred, scholarly, and literary language for more than a thousand years afterward. Its survival was not accidental. It endured because it carried authority, ritual power, and cultural memory in a civilisation that understood writing itself as divine.

As a language isolate, Classical Sumerian has no known linguistic relatives, making it structurally unique. Its agglutinative grammar allowed speakers to build complex meanings by layering prefixes and suffixes, a feature that proved especially suited to religious, legal, and mythological expression. Through Classical Sumerian, humanity’s earliest reflections on mortality, kingship, divine justice, and cosmic order were fixed in written form. Many of the ideas that later shaped Babylonian, Assyrian, and even Biblical traditions can be traced back to texts first composed in this language.

Geographic Context

Classical Sumerian developed in southern Mesopotamia, a region defined by the lower courses of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in what is now southern Iraq. This landscape of floodplains, canals, marshes, and fertile soil supported some of the world’s first cities, including Uruk, Ur, Lagash, Nippur, and Eridu. These urban centres were not only economic hubs but also intellectual and religious centres where writing, administration, and theology evolved together.

The environmental conditions of the region deeply influenced Sumerian thought. Seasonal floods, unpredictable rainfall, and the constant labour required to manage water systems shaped a worldview in which order had to be imposed upon chaos. Classical Sumerian texts reflect this tension repeatedly, portraying gods as regulators of cosmic balance and kings as divinely appointed stewards of the land. While local dialects existed, Classical Sumerian emerged as a standardised literary form used across city-states, allowing myths and hymns to circulate beyond regional boundaries.

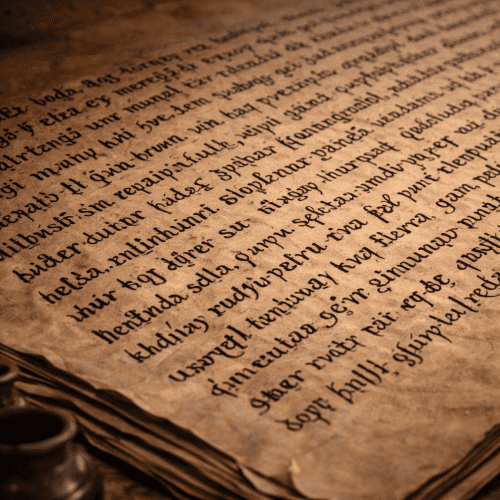

Script/Writing System

Classical Sumerian was written using cuneiform, a script developed in Mesopotamia around 3400 BCE. What began as simple pictographs gradually evolved into wedge-shaped impressions pressed into clay with a reed stylus. By the time Classical Sumerian reached its literary peak, cuneiform had become a sophisticated system combining logograms, phonetic signs, and determinatives that clarified meaning.

This writing system was remarkably flexible. It could record economic transactions with precision while also capturing poetic language, ritual formulas, and complex mythological narratives. Clay tablets, once dried or baked, proved extraordinarily durable, ensuring the survival of texts across millennia. Even after Akkadian replaced Sumerian as the dominant spoken language, cuneiform continued to be used to write Classical Sumerian in religious and scholarly contexts, reinforcing its prestige and authority.

Mythological Texts Written

Some of the earliest mythological compositions known to humanity were written in Classical Sumerian. These texts include the earliest versions of the Gilgamesh cycle, which explore friendship, grief, and the limits of human immortality. Hymns and myths dedicated to Inanna describe her descent into the underworld, presenting one of the oldest known narratives of death and rebirth. Creation myths such as Enki and Ninmah and flood narratives centred on figures like Ziusudra reveal early attempts to explain human suffering and divine responsibility.

These compositions were not isolated stories but part of a coherent mythological framework. Gods were portrayed as powerful yet fallible, capable of wisdom, jealousy, and compassion. Humanity occupied a fragile position, created to serve the gods yet capable of earning divine favour or punishment. Classical Sumerian gave these ideas a fixed literary form, allowing them to be preserved, copied, and adapted by later cultures.

Transmission & Preservation

Although Classical Sumerian ceased to be spoken in daily life, it survived as a language of education and ritual. Scribal schools known as edubbas trained students to read and write Sumerian alongside Akkadian, producing thousands of copies of older texts as part of their curriculum. Many of the tablets discovered by modern archaeologists are, in fact, student exercises, a testament to the language’s long afterlife.

During the Babylonian and Assyrian periods, scholars compiled bilingual lexical lists, grammars, and commentaries to preserve Sumerian knowledge. Even into the first centuries CE, Greek-speaking scribes were still being introduced to Sumerian through transliterations. This continuous chain of transmission makes Classical Sumerian one of the best-preserved ancient languages despite its early extinction as a vernacular.

Symbolism & Cultural Role

In Sumerian culture, language itself carried sacred weight. Writing was believed to be a divine gift, overseen by deities associated with wisdom and record-keeping. Classical Sumerian texts were therefore more than communication tools; they were vessels of cosmic order. The act of writing a hymn or ritual formula was seen as participation in the divine structure of the universe.

Symbols embedded in the language reinforced this worldview. Determinatives marked gods, cities, and sacred objects, blurring the line between writing and ritual iconography. Myths written in Classical Sumerian legitimised kingship, explained natural phenomena, and reinforced social hierarchies. Through repeated copying and recitation, these texts became anchors of cultural identity, binding communities to their gods and ancestors.

Comparative Analysis

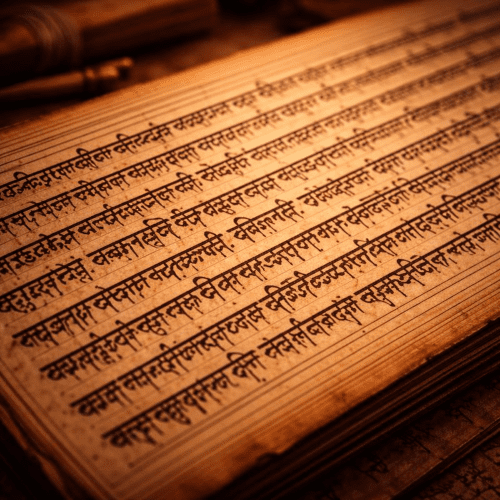

Classical Sumerian occupies a unique position in world history. Unlike Egyptian, Greek, or Latin, it belongs to no known language family, yet it exerted immense influence through cultural transmission rather than linguistic descent. Its myths parallel themes found across cultures, including creation from primordial waters, catastrophic floods, and journeys to the underworld. These motifs later appear in Babylonian, Hebrew, Greek, and even Indian traditions, though expressed through different theological lenses.

In contrast to Greek mythology, which was transmitted orally for centuries before being written down, Sumerian myths were recorded at an early stage, giving them unusual textual stability. Like Latin in medieval Europe, Classical Sumerian retained prestige long after it stopped being spoken, serving as a scholarly and ritual language that connected later generations to an idealised past.

Modern Influence

Today, Classical Sumerian remains central to the study of ancient history, religion, and linguistics. Thousands of tablets continue to be translated and reinterpreted, offering new insights into early law, cosmology, and human psychology. Concepts first articulated in Sumerian texts, such as the flood narrative or the heroic quest for immortality, continue to resonate in modern literature, film, and theology.

Digital archives and computational tools have further expanded access to Sumerian texts, allowing scholars worldwide to collaborate on reconstruction and analysis. Beyond academia, Classical Sumerian stands as a reminder that humanity’s oldest questions about existence, power, and meaning were asked long before the modern world took shape.

Sources

Britannica. (1998). Mesopotamian mythology. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Mesopotamian-mythology

Britannica. (1998). Sumerian language. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Sumerian-language

Kramer, S. N. (1999). Sumerian mythology: Introduction. Sacred Texts. https://sacred-texts.com/ane/sum/sum05.htm

Study.com. (2025). Mesopotamian mythology: Gods, creatures & stories. https://study.com/academy/lesson/mesopotamian-mythology-gods-creatures-stories.html

StudySmarter. (2024). Sumerian language: Origins & writing system. https://www.studysmarter.co.uk/explanations/history/classical-studies/sumerian-language/

Wikipedia. (2002). Sumerian language. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sumerian_language

Frequently Asked Questions

What is Classical Sumerian?

Classical Sumerian is the literary and scholarly form of the Sumerian language used in Mesopotamia from around 2900 BCE onward, long after it ceased to be spoken daily.

Why is Classical Sumerian important?

It is the earliest known written language and preserves humanity’s oldest mythological, religious, and legal texts.

Is Sumerian related to any modern language?

No. Sumerian is a language isolate with no known linguistic relatives, ancient or modern.

What myths were written in Classical Sumerian?

Major texts include early versions of the Epic of Gilgamesh, Inanna’s Descent to the Underworld, creation myths, and flood narratives.

How do we know how to read Classical Sumerian today?

Modern scholars rely on bilingual Akkadian-Sumerian texts, ancient lexical lists, and comparative analysis preserved by Mesopotamian scribes.