Hotei : The Beloved Laughing Buddha of Japan

Listen

At a glance

| Description | |

|---|---|

| Origin | Japanese Mythology |

| Classification | Gods |

| Family Members | N/A |

| Region | Japan |

| Associated With | Abundance, Prosperity, Happiness |

Hotei

Introduction

Hotei, celebrated across Japan as a symbol of joy, generosity, and effortless abundance, traces his origins to the Chinese monk Qieci (契此), better known as Budai. This real 10th-century Chan (Zen) wanderer became legendary for his prophetic abilities, carefree nature, and habit of distributing gifts from a seemingly bottomless sack. After declaring on his deathbed in 916 CE that he was an incarnation of Maitreya, the future Buddha, Budai’s story spread throughout East Asia. When Zen Buddhism took stronger root in Japan during the 13th century, Hotei’s persona blended seamlessly into its cultural fabric. By the Edo period, he was officially recognised as one of the Shichifukujin—the Seven Lucky Gods—venerated for spreading happiness and good fortune. Today, Hotei statues are found in temples, homes, and businesses, where his wide smile and open posture continue to embody a spirit of contentment cherished across generations.

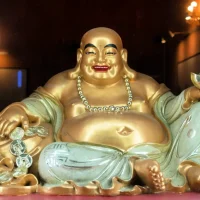

Physical Traits

Hotei is instantly recognisable through his distinct and joyful appearance. His plump figure, exposed belly, and relaxed posture reflect abundance not merely in material terms but in spiritual contentment. Artists consistently portray him bald, with elongated earlobes suggesting wisdom and compassion. His great sack, from which he takes his name, accompanies him everywhere, resting over one shoulder as he wanders from village to village. Sometimes he carries an oogi, a ceremonial fan associated with wish-fulfilment, and on other occasions he is shown surrounded by delighted children who cling to him playfully. These details capture his warmth and accessibility, while his tattered robes and bare feet reveal his Zen detachment from worldly comforts. More than a physical figure, Hotei represents an unburdened mind—free of anxiety, ego, and desire.

Family

Unlike many Japanese deities whose stories are grounded in divine genealogies, Hotei’s origins are tied to an actual historical monk who lived a solitary yet socially connected life. He is not associated with a biological family in either Chinese or Japanese tradition. Instead, Hotei’s relationships are understood in spiritual terms: his compassion links him to humanity at large, especially children, the poor, and those who seek solace in his cheerful presence. In Japanese mythology, his closest equivalent to a “family” is the Shichifukujin. Within this group—featuring Ebisu, Bishamonten, Daikokuten, Fukurokuju, Jurojin, and Benzaiten—Hotei stands out as the embodiment of mirth and simple happiness. Together, these deities sail the takarabune, the treasure ship that appears during the New Year to bless communities with prosperity. This symbolic companionship reflects Hotei’s universal role: a benevolent guardian who cares for all without distinction.

Other names

Hotei is known by several names across different cultures, each revealing a facet of his evolving identity. In China he is called Budai (布袋), meaning “cloth sack,” referencing the bag he famously carried. In Japan he is addressed respectfully as Hotei-osho, or “Priest Hotei,” while the names Warai-Hotoke (Laughing Buddha) and Smiling Monk emphasise his radiant cheerfulness. In the West he is widely recognised as the Laughing Buddha, a title that has become universal even though he is distinct from Gautama Buddha. In some traditions he is also associated with Fudaishi, a title rooted in Chan Buddhist lore. Whether in Vietnam, Korea, or further abroad, the figure of Hotei continues to carry echoes of his early identity as an avatar of Maitreya—a promise of hope, renewal, and future enlightenment.

Powers and Abilities

Hotei’s abilities are largely symbolic, yet profoundly influential. His magical sack is said to expand infinitely, providing food, toys, and treasures that he freely gives to those in need. Stories describe him predicting the future with uncanny accuracy, a skill attributed to his enlightened state. The oogi he holds acts like a celestial fan capable of granting wishes, easing hardships, or guiding spiritual seekers. Hotei is also portrayed as immune to weather, sleeping outdoors even in harsh conditions without discomfort—a testament to his complete liberation from worldly suffering. Most importantly, Hotei radiates emotional and spiritual transformation: he dispels sadness, restores optimism, and embodies the ideal that true wealth comes from an open, joyful heart. As part of the Seven Lucky Gods, he contributes the blessings of happiness, generosity, and emotional fulfilment.

Modern Day Influence

Hotei’s influence in contemporary culture is vast, spanning spirituality, lifestyle branding, décor, tourism, and popular media. His statues are staples in restaurants and businesses across Asia and the West, where he is believed to attract prosperity and positive energy. The common practice of rubbing his belly for luck reflects an intimate cultural connection to his kindness and abundance. Hotei also appears in modern wellness spaces, mindfulness programs, and artistic works where his message of simplicity and joy resonates with modern audiences seeking balance in fast-paced lives. In Japan, he remains a central figure in New Year celebrations, netsuke carvings, and temple art, while abroad he has become a global emblem of optimism. From animations to fashion prints to spiritual workshops, Hotei’s smiling figure continues to inspire a philosophy of generosity, light-heartedness, and inner freedom.

Related Images

Source

Bocking, B. (2005). The Oracles of Tsung-mi (780-841): An Introduction to his Usage of the Buddhist Sources. The International Institute for Buddhist Studies.

Dover Publications. (1986). Myths and Legends of Japan. Dover Publications. https://store.doverpublications.com/products/9780486270456

Kano, Y. (n.d.). Portraits of the Seven Lucky Gods. [Historical artwork referenced in Shichifukujin lore].

Mythopedia. (2022). Hotei. https://mythopedia.com/topics/hotei

Onmark Productions. (1994). Hotei – God of Contentment and Happiness. https://www.onmarkproductions.com/html/hotei.shtml

Sakura Co. (2024). Hotei and the Mythical Lucky Gods of Japan. https://sakura.co/blog/hotei-and-the-mythical-lucky-gods-of-japan

Wikipedia. (2023). Budai. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Budai

Faure, B. (1998). The Laughing Buddha of Zen. Princeton University Press.

Little, S. (2000). Daoism and Popular Religion in China. University of California Press.

Sharf, R. H. (1995). Buddhist Modernism and the Rhetoric of Meditative Experience. Numen, 42(3), 228–283.

Reader, I. (1991). Religion in Contemporary Japan. University of Hawaii Press.

Aston, W. G. (1972). Shinto: The Ancient Religion of Japan. Charles E. Tuttle Publishing.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is Hotei the same as the Buddha?

No. Hotei is a representation of Budai, a joyful monk later linked to Maitreya, while Gautama Buddha is the founder of Buddhism.

Why is Hotei always shown with a big belly?

His large belly symbolises happiness, abundance, and carefree living, representing emotional and spiritual fullness.

What does Hotei’s sack contain?

Legends say his sack holds endless gifts, food, and treasures he distributes to those in need.

Is rubbing Hotei’s belly good luck?

Yes. Many cultures believe rubbing his belly brings prosperity, happiness, and good fortune.

Why is Hotei one of the Seven Lucky Gods?

Hotei represents joy and generosity, contributing emotional well-being and abundance within the group of deities.