Fati : The Tahitian Moon Deity of Celestial Cycles

Listen

At a glance

| Description | |

|---|---|

| Origin | Tahitian Mythology |

| Classification | Gods |

| Family Members | Roua (Father), Taonoui (mother) |

| Region | French Polynesia |

| Associated With | Moon, Lunar cycles, Tides, Navigation |

The Mythlok Perspective

From the Mythlok perspective, Fati represents a form of divine power that modern cultures often overlook. Unlike lunar figures who embody romance or madness, Fati reflects discipline through consistency. When compared with lunar deities from other traditions, his significance lies not in mythic drama but in reliability. Polynesian cosmology, through Fati, frames balance as an ongoing responsibility, a lesson that resonates strongly in a world struggling to live within natural limits.

Fati

Introduction

Within the sacred cosmology of the Society Islands and Tahiti, Fati occupies a quiet yet essential place as the male god of the Moon. In Polynesian thought, the Moon was never a distant object but a living presence that shaped time, fertility, travel, and ritual life. Fati’s identity reflects this worldview. He is not portrayed as a dramatic creator or warrior but as a stabilising force whose steady cycles allowed island societies to live in rhythm with the natural world. Fishing seasons, planting schedules, and ceremonial calendars all followed the Moon’s movement, making Fati an unseen guide in daily survival.

Unlike later written mythologies, Tahitian traditions were preserved orally through chants, genealogies, and ritual memory. Within these recitations, Fati appears as a celestial constant, ensuring balance between darkness and light. His presence complements solar powers without competing with them, reinforcing the Polynesian emphasis on harmony rather than dominance. Through Fati, the Moon becomes a symbol of continuity, reminding humans that order is maintained through repetition, patience, and respect for natural cycles.

Physical Traits

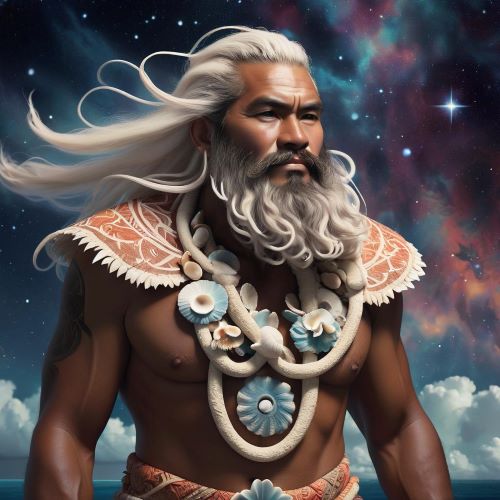

Tahitian mythology does not describe Fati with fixed physical features. Instead, his form is understood symbolically, mirroring the Moon itself. He is envisioned through luminosity rather than anatomy, appearing as pale, reflective, and serene. His presence is felt in the silver glow that cuts through tropical darkness, softening the night rather than overpowering it. This abstraction reflects a broader Polynesian tendency to define deities by function and influence rather than human likeness.

In ritual settings, Fati’s essence was evoked using white shells, polished stones, or reflective surfaces that captured moonlight. These objects were not idols but conduits, allowing worshippers to recognise lunar power without confining it to a single shape. Modern artistic interpretations often portray Fati as youthful and radiant, with fluid contours suggesting the Moon’s waxing and waning phases. This visual fluidity reinforces his association with change, renewal, and impermanence, qualities central to Polynesian spiritual philosophy.

Family

Fati’s lineage places him firmly within Tahitian cosmic order. He is traditionally identified as the son of Roua and Taonoui. Roua is associated with solar authority and celestial organisation, while Taonoui represents earthly stability and the generative foundation of the heavens. Through this union, Fati emerges as a bridge between sky and earth, embodying a balance of warmth and coolness, activity and rest.

This genealogy reflects a recurring Polynesian pattern in which celestial bodies are born from complementary forces. While some traditions link Fati indirectly to higher creator figures such as Taʻaroa, his role remains distinct and focused. There are no extensive myths describing siblings, spouses, or offspring, suggesting that Fati’s function was seen as singular and self-contained. His familial positioning emphasises responsibility over drama, reinforcing his role as a regulator rather than an instigator of mythic conflict.

Other names

Fati is occasionally referred to as Faiti, a variation shaped by regional pronunciation and oral transmission. Such differences are common across Polynesia, where dialects evolved independently across island groups. These variations do not signal different identities but rather highlight the adaptability of oral tradition. Unlike more widely travelled deities, Fati retained a relatively consistent name, likely due to his specific regional association and focused domain.

Poetic references within chants sometimes describe him through descriptive titles rather than formal alternate names, invoking him as the bearer of night light or the keeper of lunar time. These epithets function as metaphors rather than replacements, reinforcing his identity without fragmenting it. In modern scholarship and digital archives, Fati is typically standardised under a single name, preserving clarity while acknowledging oral diversity.

Powers and Abilities

Fati’s authority lies in governance rather than intervention. His primary power is the regulation of lunar phases, ensuring the Moon’s predictable cycle across nights and seasons. This constancy allowed Tahitian communities to track time long before mechanical calendars, aligning agriculture, fishing, and ritual observance with celestial rhythm. The Moon’s phases under Fati’s influence marked moments of planting, harvest, and spiritual renewal.

His lunar domain also extended indirectly to ocean tides, an influence of immense importance in a seafaring culture. While myths do not depict Fati actively commanding the sea, his presence was understood as integral to its movement. Fati’s light guided nocturnal navigation, offering clarity during voyages and reinforcing trust in celestial order. Spiritually, his cycle symbolised renewal rather than rebirth through destruction, teaching that balance is restored through patience and repetition rather than force.

Modern Day Influence

Although traditional Tahitian religion was disrupted by colonial contact and Christian conversion, Fati’s symbolism persists beneath the surface of cultural memory. Lunar awareness remains embedded in Polynesian ecological knowledge, fishing practices, and ceremonial timing. Contemporary cultural revivals draw upon lunar symbolism to reconnect communities with ancestral wisdom.

In art, tattoo design, and storytelling, Fati appears as a quiet emblem of guidance and continuity. Educational initiatives and cultural tourism increasingly reference lunar deities to explain Polynesian navigation and environmental ethics. Scholars of comparative mythology now place Fati alongside other lunar figures worldwide, recognising his role in shaping a worldview rooted in balance rather than conquest. In a modern era defined by ecological instability, Fati’s association with rhythm and restraint feels unexpectedly relevant.

Related Images

Source

Beckwith, M. (1970). Hawaiian mythology. University of Hawaii Press.

Definitions.net. (n.d.). Fati. https://www.definitions.net/definition/fati

Rjabchikov, S. (2014). On the observations of the sun in Polynesia. arXiv.

https://arxiv.org/pdf/1407.5957.pdf

Wikipedia. (2024). Lunar deity. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lunar_deity

Henry, T. (1928). Ancient Tahiti. Honolulu: Bernice P. Bishop Museum Press.

Craig, R. D. (1989). Dictionary of Polynesian Mythology. New York: Greenwood Press.

Williamson, R. (1933). Religion and Social Organization in Polynesia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wikipedia. (n.d.). Fati (god). Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fati_(god)

Frequently Asked Questions

Who is Fati in Tahitian tradition?

Fati is the male god of the Moon associated with Tahiti and the Society Islands, responsible for lunar cycles and celestial balance.

What is Fati associated with?

He is linked to the Moon’s phases, timekeeping, tides, navigation, and natural rhythms essential to island life.

Was Fati widely worshipped?

Fati was not a central creator deity but was respected for his practical influence on agriculture, fishing, and ritual timing.

Is Fati related to other Polynesian gods?

Yes, he is traditionally described as the son of Roua and Taonoui, placing him within the broader Polynesian divine hierarchy.

Does Fati appear in modern culture?

His symbolism continues through cultural revival, art, navigation traditions, and scholarly study of Polynesian cosmology.