Different Ramayana Versions and What They Reveal About Culture

The Ramayana is not a single, frozen text but a living epic that reshaped itself wherever it travelled. As stories crossed languages, kingdoms, and belief systems, new Ramayana versions emerged, each reflecting local values, aesthetics, and moral priorities. What binds them is the core narrative of Rama, Sita, exile, devotion, and dharma. What distinguishes them is how each culture chose to retell that story. This comparative exploration looks at the most influential Ramayana versions and how they diverge while remaining recognisably the same epic.

Valmiki Ramayana: The Archetypal Foundation

Often treated as the canonical source, the Valmiki Ramayana is written in Sanskrit and structured as a poetic epic. Rama here is portrayed as an ideal human who gradually reveals divine qualities rather than beginning as a god. Moral conflict is central, especially the tension between personal desire and royal duty. Sita’s trial, Ravana’s complexity, and Rama’s internal struggles give this version a distinctly philosophical tone. Most later Ramayana versions either adapt its narrative spine or consciously react against it.

Ramcharitmanas: Devotion Over Doubt

Composed in Awadhi by Tulsidas, the Ramcharitmanas transformed the epic into a bhakti text. Rama is unequivocally divine from the outset, an object of worship rather than moral ambiguity. The emphasis shifts from ethical dilemma to devotional surrender. Episodes are reshaped to highlight grace, compassion, and salvation through faith. This version became deeply influential in North India, where the Ramayana moved from courtly literature into public recitation and lived religious practice.

Kamba Ramayanam: Poetic Grandeur and Emotional Depth

Written in classical Tamil, the Kamba Ramayanam is renowned for its lyrical richness and emotional intensity. Kamban amplifies the inner lives of characters, especially Ravana, who appears as a tragic, learned, and doomed figure. Nature imagery, dramatic dialogue, and romantic sensibility dominate this telling. Compared to the Valmiki version, divinity and humanity blend seamlessly, reflecting Tamil literary traditions and Shaivite-Vaishnavite philosophical synthesis.

Adbhuta Ramayana: Sita as the Supreme Power

Less widely known but culturally significant, the Adbhuta Ramayana radically reorients the epic by elevating Sita as a manifestation of the supreme goddess. In this telling, she defeats cosmic threats that even Rama cannot. The narrative reflects Shakta theology, where feminine divine power underpins creation and destruction. This version challenges patriarchal readings of the Ramayana and expands the epic into metaphysical territory.

Paumacariya: A Moral Reinterpretation

Jain Ramayana traditions, especially Paumacariya, recast the epic through the lens of non-violence and ethical restraint. Rama is not divine but an exemplary moral man, while Lakshmana, not Rama, kills Ravana, thereby bearing karmic consequences. Violence is problematised rather than glorified. These Ramayana versions reveal how religious philosophy can fundamentally alter narrative ethics without abandoning the core story.

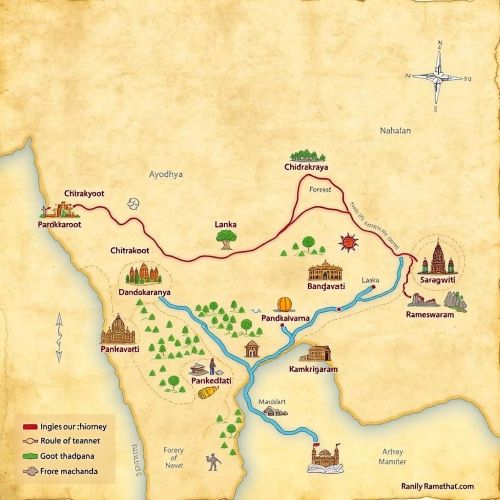

Ramakien: Kingship and Cosmic Order

Thailand’s Ramakien adapts the Ramayana into a royal and cultural framework shaped by Buddhist cosmology and Thai aesthetics. Characters wear local attire, settings resemble Southeast Asian courts, and moral emphasis is placed on kingship and order rather than personal renunciation. While recognisable, the epic becomes a legitimising myth for monarchy and statecraft, demonstrating how Ramayana versions function as political as well as spiritual texts.

Kakawin Ramayana: Harmony and Balance

In Indonesia, particularly Java and Bali, the Kakawin Ramayana integrates Hindu epics with indigenous beliefs and later Buddhist influences. The tone is less confrontational and more concerned with balance and harmony. Rama’s righteousness is measured by his ability to maintain cosmic equilibrium rather than enforce moral absolutes. Dance, shadow puppetry, and temple reliefs further transformed this version into a performative tradition.

Comparing the Ramayana Versions

Across cultures, the Ramayana adapts its moral centre. In Sanskrit and Jain traditions, ethics and consequence dominate. In bhakti versions, devotion eclipses doubt. In Southeast Asia, kingship and social harmony take precedence. Sita shifts from devoted wife to cosmic force. Ravana moves from villain to tragic anti-hero. These changes reveal that the Ramayana is less a single story and more a narrative framework capable of infinite reinterpretation.

Why Ramayana Versions Still Matter

Understanding Ramayana versions is essential to understanding how myths survive. They evolve without losing identity, absorb new philosophies without collapsing, and remain culturally relevant across millennia. For readers today, these versions offer multiple ways of engaging with dharma, power, gender, devotion, and justice. The Ramayana endures not because it stayed the same, but because it never did.

No posts were found.